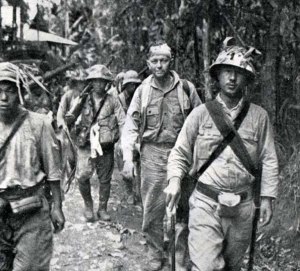

Stevenot (at right) in 1917 with the son of the first Philippine President.

On Sunday December 7, 1941, a dapper, fiftysomething American businessman climbed into Philippine Air Lines’ only Beech Staggerwing for an unusual charter flight from Manila’s Nieslon Field to a remote jungle airstrip in southeastern Luzon. Joseph Stevenot was a legend in the Philippines by this time. Born in 1888, he played a pioneering role in the development of aviation in the Philippines just after the Great War. He’d served in the National Guard and ran the Army’s aviation section on Luzon. Later, he became Curtiss’ tech rep in the Far East and established a flying school under the company’s auspices. He and one other American trained the first Filipino military aviators, flew the first aircraft into Cebu (it was a mail run) and pioneered many other aspects of aviation in the Philippines.

The box the PAL Staggerwing came in. It had been Andres Sorianos’ private aircraft through the 1930’s, and Paul Gunn had come out to Manila to be his personal pilot in 1939. Later, Sorianos and his business partners established Philippine Air Lines, and Paul Gunn was hired to be its operations manager.

In the 1920’s, he helped consolidate the many different telephone companies in the Philippines into one corporation, and he became the vice president of operations for Philippine Long Distance Telephone and Telegraph (PLTD). He made many friends in high places, and his family’s connections back in California also played a role in his many successful business ventures, including a mine operation company he started in the 1930’s. He hailed from one of the wealthiest families of the Sunshine State, where one of his brothers was perhaps the most successful hotel owner of his era and another was a senior executive with Bank of America.

He was known as a bon vivant, charming and charismatic. He moved easily through Manila’s high society, where his comings and goings were reported by the local press. In 1936, he was one of seven men who officially established the Boy Scouts of the Philippines, and he took an interest in scouting through the next five years.

The PAL hangar at Nielson Field, the Staggerwing at right.

In July 1941, Stevenot was back in Washington D.C., and he met with Secretary of War Henry Stimson to urge him to build a closer relationship with the commanders in the Philippines. He advocated for a higher defense budget for the islands as well on other occasions.

Through all his entrepreneurial efforts, he remained an Army reservist. He’d been a major for almost twenty years as he built out his life in Manila.

In the fall of 1941, Stevenot and PLTD played a key role in the development of the USAAF’s air defenses in the Philippines. Radar sets had just started arriving in the the islands, but it would be months before radar coverage would be anywhere near adequate. To spot incoming Japanese aircraft, a broad network of aerial observers was established, similar to what the British had during the Battle of Britain in 1940. These posts were scattered all over Luzon and manned mainly by Filipinos. Stevenot oversaw the construction of the phone lines that tied all this vital network into the air plotting center that had just been built at Nielson Field that fall.

On December 7th, Stevenot flew in the PAL Beech to a tiny jungle airstrip right on the water at Paracale, a tiny mining community a hundred and twenty miles southeast of Manila. Paul “P.I.” Gunn piloted the Staggerwing that day right into a raging storm that had turned the Paracale area into a sea of mud. When they touched down there, the Beech was damaged beyond local repair. Parts were later brought out to it, the plane repaired and flown back to Manila.

The next morning, Monday December 8, 1941, Paul Gunn learned of the attack on Pearl Harbor and made an epic trek back to Manila by boat, train and bus in order to be with his family. But Stevenot stayed behind at Paracale for almost a week.

What was the sixtysomething businessman doing out there on the coast that was so important Paul Gunn had to fly him through a near-monsoon to get him there?

As I’ve been writing the initial chapters of Indestructible, my biography of Paul “Pappy” Gunn, Stevenot’s trip has both fascinated and frustrated me. His letters archived at the University of the Pacific in Stockton, CA., make no reference to that trip. He just wrote his family that he was doing interesting stuff that he couldn’t talk about.

There were a series of gold mines at Paracale that I thought may have been the reason for the trip out there. The PAL Beech made weekly runs to the strip there to carry out about 125 lbs of gold per flight, but making that trip on a Sunday in terrible weather seemed unlikely . Perhaps Stevenot had a crisis he needed to handle at one of the mines his company operated? Nope. I tracked down the ownership and operating companies of those mines and discovered that none of them were run or owned by Stevenot’s corporation. His mining operations were all further south.

Then I made a startling discovery. The USAAF had sent a detachment from an early warning company out to Paracale, by ship to establish two radar sites in the area. One was supposed to be a permanent facility using an SCR-271 radar that had arrived in the Philippines that October. The other was a mobile set similar to the one seen in the movie Tora Tora Tora.

Then I made a startling discovery. The USAAF had sent a detachment from an early warning company out to Paracale, by ship to establish two radar sites in the area. One was supposed to be a permanent facility using an SCR-271 radar that had arrived in the Philippines that October. The other was a mobile set similar to the one seen in the movie Tora Tora Tora.

The men in that detachment were unhappy campers. When they reached Paracale, there were no facilities of any kind for them. They’d basically been thrown out on the edge of nowhere without any logistical support, or even a place to stay. The NCO’s were able to find a partially empty warehouse, and the men ended up calling that home for the next several weeks. Meanwhile, the det commander, a brilliant electronics specialist named Lt. Jack Rogers, bunked down in one of the mining company’s club houses. That was relative luxury compared to what the men were dealing with, and that caused a lot of internal rancor that lingered for decades.

Stevenot was not only a telephone and telegraph expert, but he’d overseen the construction of teletype networks and radio telephone facilities all over the Philippines. He’d set up the first trans-Pacific phone line to the the United States, and in the early 30’s he’d made headlines when he and eleven of his family members carried on a party line phone conversation from all over California and Manila.

In short, Stevenot was an expert in modern communication systems.

Rogers’ air warning det had taken the mobile radar set, an SCR-270, and dragged it up the side of steep mountain overlooking the water outside of Paracale. They’d set it up and got it running on December 6th, but only Rogers knew anything about how to use it. The men were so untrained that later they missed the signature of a B-17 coming over them en route to Legaspi. Only when it buzzed right over their heads did they learn of its presence in their airspace. They’d also had no time to calibrate the fussy electronics, which made it virtually useless even with operators who knew how to make it work.

There was no phone lines tying the mobile site to the plotting center at Nielson. All communication from Paracale to their chain of command back around Manila was conducted by radio, which problematical thanks to the rugged mountains in the area.

The SCR-271 set was supposed to be the basis of a permanent air warning site, but it had not been uncrated by December 8th when the Japanese attacks began. But, all the sites were supposed to be tied into Nielson via the same sort of phone adn teletype network the observer stations and other bases used.

Paracale did have phone service, so Stevenot was probably out there on December 7th to check out the new det and figure out ways to get better commo to their mountainous post.

Of course, it was too little, too late. The Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor that Monday Philippines time, and by lunch, Clark Field lay under a towering cloud of smoke and flames. Stevenot stayed at Paracale and even reported (by phone) sighting a Japanese invasion force off shore on December 13th.

Lt. Rogers’ det was ordered back to Manila after the Japanese landed in Southern Luzon. Much of the equipment was lost–abandoned or blown up as the Japanese approached, and several members of the det were either killed in action or were separated from their brothers and ended up fighting on as guerrillas. The rest made it back to Manila in time to retreat into Bataan. Those who survived the next four months endured the Death March, captivity and the Hell Ships.

Stevenot returned to MacArthur’s headquarters and retreated to Corregidor with the general’s staff at the end of December. He arrived on the Rock with a big box labeled “Signal Corps Tubes.” Actually, the box was full of good hooch, which General Charles Willoughby never forgot. In his post-war memoirs, Willoughby wrote about Stevenot busting out shots of his good stuff whenever morale was down or the FilAmerican Army had suffered another bad day.

Meanwhile, Stevenot kept a direct line open from the Manila switchboard to the yacht basin on the Rock. He would go down there and talk to his fearless employee, a female operator, who used the line as a way to eavesdrop on Japanese military conversations. After taking Manila, the senior Japanese officers used the phone system like anyone else, and those conversations yielded a gold mine of intelligence until February 1942. By then, word of how the Japanese were treating the local Filipino population had reached MacArthur’s staff, and Stevenot decided he couldn’t keep endangering his employee. He’d learned that a niece of his in Manila had been seized and tortured by the Japanese in an effort to get her to reveal Stevenot’s location, and that might have contributed to his caution in this case.

Stevenot remained on the Rock until almost the very end. But after MacArthur made it to Australia, he personally ordered Stevenot out on one of the last submarines to reach Manila Bay. He was evacuated just before the Japanese landed on Corregidor in May.

Stevenot remained on the Rock until almost the very end. But after MacArthur made it to Australia, he personally ordered Stevenot out on one of the last submarines to reach Manila Bay. He was evacuated just before the Japanese landed on Corregidor in May.

He served through 1942 and the spring of 1943 throughout the SWPA, never revealing to his family what role he was playing on behalf of MacArthur’s GHQ. He was promoted to LTC then full bird colonel. In June 1943, he died in a plane crash in the New Hebrides Islands. MacArthur wrote a personal letter of condolence to his widow.

Despite searching through the GHQ records at the MacArthur Memorial, I’ve been unable to determine exactly what Colonel Joseph Stevenot was doing for the U.S. Army in 1941-43. Lists of officers and their official positions do not include him. Yet, the Japanese knew who he was and were anxious to find him. Whether it was for his role as a civilian senior executive, or for his military role remains a mystery, as does so much of his last two years of life. Whatever the case, MacArthur deemed him an essential officer who could not be allowed to fall into Japanese hands. And the Japanese considered him so important they tortured at least one woman to try and locate him.

So, I thought I’d do this: If anyone has any further information on Joseph Stevenot, I would love to hear from you. While he is just a passing character in the book I’m writing, his fascinating life and accomplishments have become of great interest to me. In the meantime, he’ll remain the mysterious major of Indestructible‘s early chapters.

John R. Bruning

Telecommunications expert plus someone with a knowledge of radar in 1941! What a great catch he would have been for Japanese intelligence. I am surprised that we took so long to get him out. Makes me think someone was sleeping on the job.

I am curious if you ever came across the name Fletcher Wood in your research. He was a mining engineer in the Philippines who ended up in the Army Corps of Engineers and Corregidor. He died in Bilibid. I would be grateful if you could contact me. I also maintain a blog http://americanpowsofjapan.blogspot.com

Mindy,

Was Fletcher Wood at Paracale at the start of the war? If so, I may have seen some references to him in the interviews I have. Did he become a lieutenant when he was first pulled into the Army?

Thanks for writing, and your blog is amazing!

John R Bruning

John,

Good afternoon. Curious if you have come across the name John Gilmore in your research. He was Pappy’s best friend 42-45 (cut Pappy’s finger off, flew on 1st 75mm flight, restored Gunn family et al) as well as a policy maker for all airmen of the Pacific War. I cared for him for the last 10 years of his life including buried him with full military honors (including B-25 flyby).

Best-

Bradley

Bradley,

Thanks for writing! I have come across John Gilmore’s name many, many times. I found a medical evaluation report he wrote in 1943 regarding Pappy’s condition & mental state after Bismarck Sea. I’d love to talk to you sometime about John. johnbruningjr@yahoo.com

Thank you!

John

John:

Thank you and lets do it. Just wrapping up a project. How does next week work? Please advise when convenient.

All the best-

Bradley

Stevenot called on MacArthur on 16 October 1942, in the company of Col. Reddick and Lt. Col. McDaniels. A Col. Reddick was a successful Illinois printer who ran the forgery section of OSS in Europe. MacArthur’s desk diary doesn’t give the men’s initials, so I can’t establish a link between this visit and Wild Bill Donovan’s “Penetrate MacArthur” campaign, but it might bear investigating.

Hi Karen,

That is fascinating. Thank you for the information. If I come across anything else, I’ll let you know!

John

Unfortunately, I found another visit, this time it is spelled Rodieck. If you google Roedieck and McDaniels you can read about their much more mundane visit. They are identified “of the War Dept.”

There is a nice anecdote by Gen. Wiloughby. He heard of Stevenot’s death but then received a present from him. Stevenot had had personalised matchbooks made for him with the Army seal and is name. He was touched by the thoughtfulness.k