In August 2009, Specialist Taylor Marks was killed by an Iranian-made EFP roadside bomb emplaced on a bridge in downtown Baghdad only a short distance away from an Iraqi Police checkpoint. Killed with him was Sergeant Earl Werner, a veteran of OIF II and the Oregon National Guard’s relief efforts in New Orleans following Katrina. I did not know Sergeant Werner, but I knew of him. Taylor, on the other hand, was like family to me. Before he left our little Oregon town, he had routinely babysat my kids. He introduced my son to LEGO’s and showed them you could set stuff on fire with a magnifying lens and some sunlight. That was the Puckish side of him–he liked to push boundaries, but never so far that he got out of line. His teen age rebellion consisted of exploring abandoned buildings at night, playing with fireworks, and building modified potato guns that could fire simulated RPG’s at 2-162 Infantry’s Humvees during drill weekends.

In August 2009, Specialist Taylor Marks was killed by an Iranian-made EFP roadside bomb emplaced on a bridge in downtown Baghdad only a short distance away from an Iraqi Police checkpoint. Killed with him was Sergeant Earl Werner, a veteran of OIF II and the Oregon National Guard’s relief efforts in New Orleans following Katrina. I did not know Sergeant Werner, but I knew of him. Taylor, on the other hand, was like family to me. Before he left our little Oregon town, he had routinely babysat my kids. He introduced my son to LEGO’s and showed them you could set stuff on fire with a magnifying lens and some sunlight. That was the Puckish side of him–he liked to push boundaries, but never so far that he got out of line. His teen age rebellion consisted of exploring abandoned buildings at night, playing with fireworks, and building modified potato guns that could fire simulated RPG’s at 2-162 Infantry’s Humvees during drill weekends.

Taylor armed with one of his RPG simulators at Fort Lewis in June 2008, his last volunteer OPFOR drill weekend before leaving for Basic Training.

He was a brilliant young man who had earned a scholarship to the University of Oregon, where he planned to become an Asian Studies major. But after meeting me and my band of rag-tag civilians who role-played bad guys for the Guard and law enforcement, Taylor chose a path of service. He joined the Guard straight out of high school and was training to be a military intelligence specialist when the 41st Brigade departed Oregon for its pre-deployment work up at Camp Shelby in the spring of 2009. Taylor originally had orders to attend the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, California, but the 41st was so short handed those were changed at the last minute. Instead, he was pulled into the 82nd Cav and assigned to be an MRAP driver.

Taylor’s senior prom night. I let him have my Pontiac GTO for the night. He’s one of about six people to have driven the car, and it escorted his remains home from the airport, then to Willamette National in 2009. The GTO will never leave my family as a result.

He reached Oregon in early June of 2009 having not fired a weapon in months. During one of our OPFOR drill weekends at Camp Rilea, Oregon, I asked some of the NCO’s there if they could get Taylor some range time since he’d missed almost all the pre-deployment training with his new unit. About two weeks later, Taylor was sent to Camp Shelby just in time to help his unit pack up and head out the door for Iraq. He was killed in action six weeks later.

The 973rd Civlians on the Battlefield (COB). Taylor is standing at top right.

His death in combat was one of those terrible turning points in my life. I lost a young man who’d become a major part of my family’s life, whose life had been set on the path to Iraq by his association with me. Intellectually, I knew his death was not my fault. But in my heart I knew that had I not drawn him into my group of civilian volunteers and introduced him to the National Guard, he’d have gone off to college like so many other young men. My heart will always be burdened with that guilt, and it took me almost five years to reconcile and accept that burden of responsibility. I also learned that the pain of loss never goes away; it just becomes a part of you that either you accept and live with, or it will torment and destroy you. It was a toss up which way it would go with me for a long time. Part of me went to Afghanistan to tempt Fate. If God wanted to take Taylor, then take me too. He didn’t. I came home, and Taylor didn’t, and for a long time that made his loss even harder to bear. It colored every day, and for a long time, it took down much of the best parts of my life. In my eulogy of him, I promised to live my life for him, as adventurous and wide open as he had led his. I took that vow as sacred, and have tried to live up to it, but there were times in the first years after his death that I very nearly gave in to the grief and guilt.

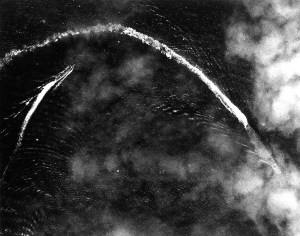

Gerald Johnson (at right). MIA October 7, 1945. He was lost in a typhoon off the coast of Japan less than a week before he was supposed to rotate home. He’d survived over 1200 combat hours and 265 missions in three tours that spanned the Aleutians, New Guinea and the Philippines.

In the 1990’s, I became very close to 49th Fighter Group ace Colonel Gerald R. Johnson’s widow, Barbara. Like Taylor, she had become part of my extended family, and had even been part of my wedding party in 1993. While writing first my M/A thesis on her beloved husband, then the book Jungle Ace, my time with her was precious and life-changing. It was also the first time I really began to understand the magnitude of such a loss. Five decades had passed since she had lost Gerald at war’s end, but his death had altered the landscape of her life so profoundly she lived in its shadow for the rest of her life. The grief never went away. Time does not heal all wounds. In Barbara’s case, it perhaps dulled the pain a little bit, but it was always there in her eyes.

Shilo Battlefield.

So this Memorial Day, there will be countless pundits speaking of the “ultimate sacrifice” and the bravery of our warrior heroes. Sacrifice will be so overused that it will lose its meaning. For me, Memorial Day has become a reminder of pain, of my own experience with loss, of the pain I saw in Barbara’s eyes and so many others whom I’ve met over the years who lost a beloved family member to war and violence. I will remember the elderly neighbor we had when we first came to Independence. She lived alone and was very isolated from the community. When I came to her door canvassing for a political cause, she welcomed me inside and we talked for quite a long time. She had married young, during WWII, to her high school sweetheart. Before he left for overseas service, they had a daughter together. He was killed in action, and she never remarried. What was the point, she had said to me. Her Love had died. She focused on raising her daughter and lived the rest of her life in quiet loneliness, waiting to be reunited with her Soldier.

I am typing these words right now in the Saratoga Public Library in Saratoga, California. I grew up here in the heart of the Silicon Valley back in the 70’s and early 80’s. This library was my refuge, and it was here that my love of history and writing took hold and flourished. I spent countless hours after school here, reading everything the library had collected on World War II, lost in the romance and adventure of air battles, aces and the nobility of service.

I look back now and realize that I never understood the reality of combat and what that does to the human soul. It took losing Taylor and seeing the fighting in Afghanistan for me to catch a clue and glimpse that reality. Now I understand that the death of a warrior is not only the end of a life and the destruction of so much potential, but the turning point in every life close to the lost Soldier’s. That death will have a cascading effect on those left behind that is rarely discussed or understood. For the Johnson family, Gerald’s death led to such anguish that his twin brother Harold ultimately took his own life. The shock of that led to his father’s death only a few weeks later. For me, it was the end of what I call my old life and so much in it that I loved. My sense of family changed forever, I lost friends and relationships. Like so many others, the death of an American warrior redrew the fabric of life back home. The ripples of loss spread across families, neighborhoods, communities. One by one, they redraw the face of America until, by war’s end, we find ourselves a changed nation.

When I think of Taylor now, I think of all that our nation lost when that EFP took his life. Had he lived, what amazing things he could have done with his mind and talent. The way he could have added to our collective experience, the way he would have found meaning in his life surely would have led to the betterment of the world in some small but notable way. His was one of thousands of lives cut short since the towers fell, one drop in an ocean of lost potential torn from us by an enemy who would strike at our children and our own homes if given a chance. Devoted men and women who believe in our nation’s exceptionalism and have the courage of their convictions to stand strong in the maelstrom of combat are among America’s most valuable souls. On this Memorial Day, as we mourn for those we lost, let us hope our nation’s leaders remember their value and pledge to ensure that when they are called to battle again in the future, the cause is the measure of their commitment.

To all of you hurting on this Memorial Day Weekend, all I can say is don’t lose the Faith. If you do, our nation is lost.

2nd Battalion, 162nd Infantry, Oregon National Guard. Camp Rilea, October 2008. Mobilization Day for the unit’s second deployment to Iraq.

Below is the eulogy I gave at Specialist Taylor Marks’ memorial service in Independence, Oregon in September 2009.

============================================================================

Over a century ago, Walt Whitman wrote of his experiences in the Civil War, and its aftermath.

To the tally of my soul,

Loud and strong kept up the gray-brown bird

With pure deliberate notes spreading, filling the night.

Loud in the pines and cedars dim,

Clear in the freshness moist and the swamp perfume,

And I with my comrades, there in the night.

While my sight that was bound in my eyes unclosed

As to long panoramas of visions.

And I saw askant the armies,

I saw as in noiseless dreams hundreds of battle-flags,

Borne through the smoke of the battles and pierc’d with missiles, I saw them.

I saw battle-corpses, myriads of them,

And the white skeletons of young men, I saw them,

I saw the debris and debris of all the slain soldiers of the war,

But I saw they were not as was thought,

They themselves were fully at rest, they suffer’d not.

The living remain’d and suffer’d, the mother suffer’d

And the wife and the child and the musing comrade suffer’d,

And the armies that remain suffer’d.

Taylor Marks made the transition from boy to man, first by training soldiers, then by joining them in battle. During this cornerstone period in his young life, I had the singular joy, pride and kinship to be touched by Taylor’s bright and dawning spirit.

Winston Churchill, not the statesman, but the American novelist, wrote about how disorienting this voyage from child to man can be.

At all events, when I look back upon the boy I was, I see the beginnings of a real person who fades little by little as manhood arrives and advances, until suddenly I am aware that a stranger has taken his place.

No stranger ever took Taylor’s place. To his last breath, he remained gentle of heart, loyal to those he loved, faithful to our Lord, and true to the values he had established long ago, thanks to the guidance of his family. He never lost his idealism. His spirit was never tarnished with bitterness or regret. He loved the Guard and his blossoming role within it. Unlike Churchill’s character, he negotiated the path to adulthood not to look into a mirror and see a stranger, but to see the eyes of the man he wanted to become. What a gift. So few of us get there, especially so fast, that I found myself in awe of Taylor.

Two things brought Taylor and I together: a Christmas card and a ballroom dance class. These two disparate moments in our lives formed the nucleus of our bond. In the months that followed, it was solidified and nurtured through shared misery and the sheer uniqueness of our common goals.

In December of 2007, I was sitting on my couch. My then six year old boy, Eddie, was nestled next to me, babbling on about all the World War II airplanes he wanted for Christmas. My wife Jennifer, handed me a beige envelope. It was a Christmas card from Ken Leisten Sr. Kenny, his son, was killed on July 28, 2004 in the Sunni Triangle. I wrote about him in The Devil’s Sandbox, and every July, I go to Willamette National to be with Vince Jacques and the rest of Kenny’s platoon to celebrate his life.

I sat and read this card from a man who had lost his only son, while my only son’s arms were tight around me. I started to cry, partly for Ken’s loss, but also for my own utter selfishness.

What had I done to see that no other father loses his boy? I had reams of tactical information on the enemy from the books I’d researched and written. Time had come to put it to use.

The previous May, Brad Bakke, Aaron Allen and I had role played insurgents during an Alpha Company, 2-162 Infantry drill weekend. Being an insurgent was brutal. I was sick for a month afterward.

Alpha Company asked us back for the January drill. I said I’d be there with a group ready to be abused.

At the time, I’d been asked to teach a ballroom dance section in a PE class at Central High. Most of the kids weren’t really all that into learning how to swing and waltz, but I noticed one kid had game. Every period, he came eager to learn, willing to give something new a try, and seemed devoid of self-consciousness and immune to the vibe sent out by his peers that this just wasn’t cool.

That was Taylor. He had these absolutely bizarre sideburns and chin fuzz that made me wonder if he’d taken the pilgrim section in his history class a little too seriously. But that could be, and later was, shaved. What moved me about this kid were his eyes—dark and wide, they radiated curiosity. They had depth and a sort of grace found only in much older men totally at peace with themselves. I saw in their depth, keen intelligence and a thirst to explore the world.

I didn’t see selfishness. I didn’t see a sense of entitlement. I didn’t see a kid who’d succumbed to pop culture’s fixation on the superficial or the material.

And I also sensed a bit of Puckishness in him. I liked that. I liked that a lot.

Just before Christmas vacation, I assembled the class and told them I was forming a group dedicated to helping train 2-162 Infantry for its next combat deployment overseas. I told them we would be roughed up, we’d be working in all manner of weather conditions, and we would be taxed to the utmost of our endurance. I didn’t sugarcoat this. I made it clear it would be a challenge, but one with tremendous rewards. Our goal: prepare those who fight so that every one of them comes home to their families.

Taylor was all over this. He wanted in, and was willing to bring friends. I checked with my wife, who had Taylor in her math class, and she gave me the thumbs up. Outstanding kid, good grades, sense of responsibility. He would not goof off.

Taylor brought Gaelen Bradley into our group. As the January drill approached, we wanted to make a statement to the Oregon Guard that we would not be your average weekend enemy force, or OPFOR. I scheduled us to support two companies: Alpha down in Eugene, and Charlie at Camp Whithycombe up in Clackamas. To pull this off, we’d need to go all weekend with minimal sleep.

That Saturday rolled around, and I kept Taylor and Gaelen close to me in the shoot house at Goshen. Each fire team through the door had to make a split-second decision based on our reactions to them: greet us as friends, detain us as suspects, or shoot us as hostile insurgents.

When Sergeant Alan Ezelle first told us to be hostile and resist detention, I watched Taylor get slammed face-down into concrete and broken glass. After that iteration, I thought he’d be done. He got up grinning. Gave me a thumbs up and grabbed one of our training AK-47’s, and made ready to give the next fire team.

It started to rain. Then it snowed. The shoot house has no roof, and the concrete floor soon was slick and covered with icy puddles. None of us had the sense to wear cold weather gear. Taylor’s teeth chattered. His lips turned blue. I told him to go take a break and get warm. He said, “Hell no. Bring it.”

And so it went. Fire team after fire team. Squad after squad. Taylor was dumped, dragged, shot at with blanks at close range, and generally pummeled into submission. Sergeant Ezelle didn’t make us friendly local nationals that often, so we did a lot of fighting in the snow that day. We learned one of the nuances of being an enemy force in training: you’ve got to bring the appropriate level of violence to each squad based on their level of experience and ability. As they learned and got better, Sergeant Ezelle had us ratchet up our resistance.

When the day ended, Soldiers came to us and thanked us. “You’re the most realistic OPFOR we’ve ever had.” Others said, “That’s the best training weekend I’ve had since joining the Guard.” We would hear that a lot in the months that followed, and every time such words served as rocket fuel to our motivation.

That evening, sore, stiff and soaking wet, we climbed into our cars and drove home, changed, then sped to Withycombe in time to dig shallow firing positions and execute night ambushes on Charlie Company. We finished at 3:30 that morning. Taylor was still grinning.

By the end of the weekend, our group had put in 37 hours and had impressed 2-162 enough to give us civilians a role at every field drill. Taylor and Gaelen, and Bethany Jones and Shaun Phillips set the standard for our group.

We incorporated as a non-profit called the 973rd COB—Civilians on the Battlefield. In the months to come, we spent out of our own pockets tens of thousands of dollars on equipment, clothing, and training devices. SimplyIslam.com must have wondered if a Mosque had opened up in Polk County after all the orders we placed for Arabic clothing. My office is so heaped with training AK-47’s, RPK’s, and other gear that it has become known as the Unawriter’s Lair.

When Taylor saw Alpha Company had limited access to training IED’s, he and Shaun Phillips went to work. They built simulated car bombs that when detonated, touched off a siren. When nine soldiers were killed or wounded entering an Al Qaida safe house in Iraq in early 2008, I got word from a friend over there that the place had been wired with an IR-triggered bomb that went off when the door was breached. Taylor and Shaun constructed a duplicate, and we employed this tactic against Alpha Company so they could develop counters to it.

When we started ambushing Humvee convoys at Rilea, we didn’t have access to simulated rocket propelled grenade launchers. The dreaded RPG’s. Taylor went off and built two. I’ll never forget the first time we tested one of them. We were down at Riverview Park. We wanted a projectile that would travel far enough to be useful and make a loud enough noise on impact to let the Soldiers in the Humvees know they’d been hit. At the same time, we didn’t want to use anything that could cause an injury. That is an engineering challenge way beyond me.

Taylor came up with miniature nerf footballs as ammo, squished and wrapped in duct tape. I was skeptical, and dared him to hit my GTO from about 200 feet. I got in and drove it at a steady clip, and he let loose on me.

THUNK! The Goat shuddered so hard I thought the whole right side had been bashed in. Taylor had hit the Pontiac’s real quarter panel. That was the last time we used my muscle car for target practice. Taylor’s stuff worked, and it worked in the field because he designed them to be rugged. He paid for all the materials out of his own pocket, with money that he earned from his job at the Chevron station on 22.

Every drill weekend, Taylor was there, setting a quiet example with his relentless work ethic. As he came to understand the Soldiers and what they would face in the months to come, he grew ever more dedicated. At Rilea, and at Goshen, we didn’t leave the field until the last Soldier had come off the lanes. Taylor was almost always the last man off with me.

He came to respect, then revere the NCO’s who worked with us. Sergeant Ezelle, Sergeant Hambright, Sergeant Cochran—they became Taylor’s role models. He saw in them a willingness to confront evil on distant shores. He saw in them the consummate professional NCO—capable teachers, disciplined human beings, and men capable of telling a story or two about their wild days.

Taylor asked me to be one of his mentors on his senior project, which he produced on our group. I was honored, and he’d come over to my office and we’d have some pretty serious heart to heart talks. He’d received a scholarship to the U of O and had been set on a course much like mine at his age: college, dorm life, the intellectual challenge of academia.

But he found his true calling with us. The combat arms of the U.S. military represents one tenth of one percent of our population. The fate of nations—our nation—rests on so precious few who are willing to bear this burden and forgo the advantages of an average civilian life.

As he saw the commitment 2-162’s men shared, he felt it grow within him. Once, at Andy’s, he wondered out loud how he could go to college when something so much larger needed good young men.

When he defended his senior project, I sat in the back of the classroom and felt like the proudest parent in the world. He nailed it, too, by the way.

That spring, the 973rd assembled the most outrageous and diverse group of individuals I’ve ever been associated with. Everyone understood the importance of the mission and took our responsibility in every field exercise very seriously. But along the way, the unexpected happened. We went from strangers to family in a drill weekend.

I always wanted an extended family. My own back in California is a mess, and I always sort of felt alone and left out of something most others share.

The 973rd became my crazy, boisterous, clan, bonded by the oddity of our undertaking, and the scores of hours spent in the bushes with each other waiting to ambush the next patrol. Taylor became a brother, a son. So did all our young men—Spencer, Joe, Andrew, Aaron, Gaelen—just to name a few. Joey became our spiritual center—irreverent yes, but a shoulder and an ear for everyone—including Taylor. Mark Farley our XO, balanced us, kept the peace when things got rough. I was the leader, always demanding that we be better than perfect on every iteration. And Jones too care of us all.

One day, that spring, Taylor asked me to hook him up with a recruiter I trusted. I gave him a copy of the Devil’s Sandbox and told him to read it. He came back, more resolved than ever. I wanted him to know—to understand what was at stake and the perils of the warrior profession. I gave him House to House. He read it and badgered me some more.

I was too slow for him. He went and got a recruiter on his own. Sergeant Ben Taylor played it absolutely straight with Taylor. But I completely freaked out. In front of my kids, I called Ben and tore into him and screamed things to him I’ve never said to another human being. I was protecting my cub. I later sat down with Ben and his boss, Colonel Myer, and found that my preconceptions were all wrong. Ben is a compassionate, dedicated member of the Oregon Guard, and he came to love Taylor as much as the rest of us. Ben is one of the most honest and straight human beings I’ve ever known.

After Taylor scored a 98 out of 99 on the ASVAB, he found a way for Taylor to use his love of language and Asian culture for the benefit of the Guard. He was set to go become an interrogator and a linguist, with Cantonese and Japanese as his specialties. Ben’s stewardship sent Taylor’s morale through the roof.

School was coming to an end, and I wanted Taylor’s final weeks to be memorable. That spring, during an Alpha Company drill at Goshen, he dragged his white sedan down to the range to be used as an obstacle the Soldiers would have to search.

What kind of a high school kid offers up his wheels for a training exercise? I never would have been so gracious. The car took a beating, and Taylor never once complained.

To honor that, I let him borrow my GTO so he and Gaelen could double date to the Senior Prom. Aside from my wife, who keeps breaking it, Taylor was the only other person to drive this car. That Pontiac means a lot to me. It was the first totally frivolous thing I’d ever purchased in my adult life. Up until recently, we never had the resources to be frivolous, we were lucky to keep our house. My wife had faith that I could make it to New York as a writer—and she was the only one who kept that faith—and the GTO became my reminder of our shared success.

Taylor treated my Goat with reverence. I gave him the keys, told him to keep it under eighty—yeah right—and have fun. Later that night, I grabbed the family and piled into our other Pontiac. “Where are we going?” Jenn asked. “Gonna check on the Goat.” I said.

That was the first time I’d ever been in the Green Villa Barn’s parking lot. The senior prom was held here. A year later, we’ve returned to the location of one his best high school memories to honor what he has meant to us.

Now, we are left to grieve. Thank God I don’t have to do that alone. The 973rd gathered Friday night to share this trauma equally. We visited Taylor’s family, and Michelle, Don, Morrey and Courtney—with your grace and gentle spirits you gave us the greatest gift one human can bestow on another: the ability to heal from this loss. Had we not come together as we had, had I not felt the warmth of your embrace and heard the things Taylor said of me from your own voices, I would have been done. The guilt, the pain—it would have been too much. Instead, your open home, and your open hearts laid cornerstone for a new beginning for all of us.

You also gained my extended family, my clan. Courtney, you now have a big sister in Jones and twenty older brothers. If your boyfriend breaks up with you, call us. We’ll go beat him up. This connection will bind us forever.

That connection began Taylor became one of our own. He babysat my little boy and little girl. He taught them to melt stuff with a magnifying glass, and now I have two pyromaniacs who go nuts on the 4th of July. That’s okay, so do I. He showed them how to use my treadmill for things other than exercise.

One day, he brought a big tub full of Legos over to my office. We’d never given Eddie Legos before, which Taylor thought was appalling. So he gave my boy his childhood collection. Overnight, Eddie went from a WWII airplane fanatic to a Lego-obsessed construction foreman. My office became a cityscape, complete with sharks eating Indiana Jones and elaborate space ships docked on my furniture. Just walking around without puncturing a foot on these things became a challenge. A year and a half later, Eddie’s urge for Legos has only grown. That’s all he wants for birthdays and Christmas now, and we’ve grown Taylor’s original collection significantly, partly because one of my other adopted sons, Andrew Bowder, contributed his childhood sets to the cause as well. Someday, I hope Eddie’s son will play with them, too. Grandpa’s job will be to tell him about Taylor.

We spent a year with the 2-162 and participated in every field exercise here in Oregon as they prepared to go to Iraq. We learned how to test each squad. We exploited mistakes so we could impart lessons. We figured out gaps in fields of fire and helped each squad hone their skills so such errors were ironed out here, where it didn’t count, instead of learning them with casualties on the battlefield. We earned the respect of every Soldier who went through our lanes.

About two weeks ago, I heard from Sergeant Ezelle. He’s in Iraq now, and I asked him if our group really made a contribution, and what we could do to improve for the next unit we help train. Easy wrote back, “You helped my men more than your group will ever know. Thank you.” From a two deployment veteran, that meant everything. He also added, “You need to start charging the Guard.” Never. We will never take a dime.

We now support other elements of the Guard, as well as the state police, local law enforcement and SWAT Teams. What Taylor helped found has grown beyond all our expectations. And we stand ready to help prepare those who fight anytime, anywhere.

Forming and leading the 973rd has been the most meaningful experience of my life. If we helped to save one Soldier’s life, there is nothing greater any of us will ever accomplish.

From our group, four of our young men—my adopted sons—have either joined the military, or are in the process. I live in fear of another day like this one, but at the same time I am so proud. They saw what Taylor did when we worked alongside the men of 2-162.

As Taylor prepared to leave, we sat down for lunch at Andy’s again.

I told him that he stood on the threshold of his life. The pages ahead were unwritten—he just needed to write the story. Seize, it. Go be great. Don’t lie down and succumb to the mediocrity of a life half-lived.

No worries there. Taylor was already headed that way. He was a special man, with talent, potential and drive to lead him anywhere he wanted to go. And one thing for sure, he was destined for a significant life. Where he wanted to go was into the fight, to be a member of that one tenth of one percent that keeps us safe and fights to liberate the world of all its evils. He offered his life—he didn’t give it. It was taken away by evil so vile it has scorched us all.

He lived far more in his nineteen short years than most of us will in eighty. He did so with the same wide open heart that we found in his family.

His pages will remain unwritten. And I’ve been wondering how I will survive that.

Let his spirit be our guide. Taylor went into life wide open to it. He reveled in a challenge, chased dreams and flung himself into whatever task absorbed him. There’s nothing ordinary about that.

I will live. And I will go into every day with Taylor never far from my mind. I will match his zest and daring, and I am not going to sink into the mundane. This life we all continue to share—Taylor has shown us just how precious and fleeting it is. We don’t know how many pages we have left to write in our own stories. We have to treat each one as a miracle. So, I will challenge all of you today, rise to this occasion, take with you Taylor’s spirit, and sally forth into the world with his unbeatable optimism and sense of adventure. Let it carry you to new places, let it lead you to new relationships, and may you be always be open to the wonder and beauty of this extraordinary planet.

Don’t let your job or career define you, and force you into a workaday rut that never allows for the majesty of a sunset shared with one you love. Instead, take the road less traveled, the one Taylor chose. He refused to let the world define him. He stayed true to his childhood identity even as he came to manhood. That takes a powerful, unique spirit, and it is a soul to emulate.

The successes I will have in the future, will be Taylor’s as well. He will spur me on when I’m fatigued. He will nudge me when I fall in a rut. I will dare when once I would have been cautious. And I will fill my pages for him. And when it comes time for my eulogy, let the world know that I lived true to my own soul.

That is how I will survive.

Just before Taylor left, he sent me a text message from the Blackberry he always was fooling with. “John, Thank you. That day at Central—it has changed my life for I believe the better, and no matter what happens from here, I want you to know I think it was one of the coolest decisions I have ever been able to make. I can’t wait to be OPFOR again when I get back. See you in ten months.”

We won’t see Taylor in ten months. Our reunion has been delayed, but rest assured, there will be one.

Moxley Sorrel, who served as Robert E. Lee’s chief of staff, penned these words as he tried to speak of his love for his men.

For my part, when the time comes to cross the river like the others, I shall be found asking at the gates above, “Where is the Army of Northern Virgnia?” For there I make my camp.

When I cross that river, I will find the bivouac of the Oregon Guard, because I know my brothers and sisters of the 973rd will not be far away. And there, between the two camps, I will find Taylor.