During the bitter fighting for Northern Luzon, Philippines in the final months of World War II, the 37th Infantry Division (Ohio National Guard) was tasked flanking the main Japanese positions and seizing the coastal town of Aparri. This was the scene of one of the first Japanese amphibious landings in the 1941-42 campaign. General Walter Krueger decided to commit elements of the 11th Airborne Division to the attack, which he hoped would ultimately surround one of the last major Japanese army formations on the island (Shobu Group with about 50,000 men).

The storied 11th Airborne Division was the only air assault unit available to General MacArthur’s Sixth and Eighth Armies. The men of the 11th had executed airborne landings at Nadzab, New Guinea, Noemfoor, New Guinea and had dropped on Corregidor Island right atop a garrison that significantly outnumbered them. Elements of the division at taken part in the Los Banos Raid, the liberation of Manila and had fought on Leyte and Negros Islands as well.

The 1st Battalion, 511th Parachute Infantry formed the core of the task force assembled for this new mission, but men from the 187th Infantry, the 127th Engineers and the 457th Parachute Field Artillery also joined what would be known as TF-Gypsy. The plan called for a drop and glider landing on an airfield just out side of Appari. Once on the ground, the task force would push south while the Ohio National Guard advanced north to effect the link up.

The operation began on June 21, 1945 when a small group of Pathfinders air assaulted onto Camalaniugan Airfield to prep the LZ. Two days later, on the morning of June 23rd, the men of Task Force Gypsy climbed into sixty-seven C-47’s and C-46 transports for the short flight to the LZ. As the aircraft arrived overhead, the Pathfinders on the group popped colored smoke to mark the drop zones.

Four of the six Waco CG-4’s that took part in the Aparri landing are seen here in the LZ. June 23, 1945.

Heavy winds hampered the parachutists. Two were killed and at least another seventy suffered injuries as they were buffeted by the winds and thrown into trees or other terrain features on the ground. The airfield itself was poorly developed and the uneven ground proved treacherous.

A half dozen Waco CG-4 gliders landed after the parachutists got on the ground. They carried the task force’s heavy weapons and jeeps, giving Gypsy a bit of mobility.

The task force quickly assembled and began patrolling south of the airfield, where the paratroops ran into determined resistance. For three days, the men of the 511th and 457th Parachute Field Artillery Bn (attacked to TF Gypsy), burned out bunkers with flame throwers, destroyed pillboxes with 75mm pack howitzer fire and waited for the 37th to reach them. It took until June 26th for the two American elements to link up, but when they did, the Shobu Group’s escape route to the coast had been cut off. The Japanese troops faced a grim fate: starvation, death or surrender.

The Aparri operation was the last American combat air assault operation of WWII. A number of combat cameramen joined the mission, taking extensive film and photographs while in the LZ. Below is one reel of uncut, unedited footage shot by one of those men on June 23, 1945.

This post is dedicated to the memory of Everett “Smitty” Smith, 187th Infantry, who was part of TF-Gypsy that June. His son has a fantastic blog that chronicles his father’s experience during the war. Find it at: https://pacificparatrooper.wordpress.com

Rakkassans!

In just two hours on June 15, 1944, three hundred amphibious tractors (LVT’s) carried over eight thousand heavily armed U.S. Marines onto Saipan Island in the Marianas Chain. It was a masterful display of amphibious warfare tactics and doctrine, but it also set the stage for a brutal, close range battle for control of Saipan’s sandy west coast. In places, the Marines found themselves pinned down by intense mortar, artillery and automatic weapons fire, and it took hours just to claw a foothold ashore. But by nightfall, the Marines had established themselves enough to repel the first of many Japanese counter-attacks.

In just two hours on June 15, 1944, three hundred amphibious tractors (LVT’s) carried over eight thousand heavily armed U.S. Marines onto Saipan Island in the Marianas Chain. It was a masterful display of amphibious warfare tactics and doctrine, but it also set the stage for a brutal, close range battle for control of Saipan’s sandy west coast. In places, the Marines found themselves pinned down by intense mortar, artillery and automatic weapons fire, and it took hours just to claw a foothold ashore. But by nightfall, the Marines had established themselves enough to repel the first of many Japanese counter-attacks.

This short film clip is raw footage shot by one of the Marine combat cameramen who went ashore with one of the first waves. It is silent, as was most of the footage shot, but that only adds to the poignancy of these scenes. The images are striking, not only for the chaos and carnage they reveal, but also for the film’s clarity. Much of the Marine Corps color footage has deteriorated over the years so that they are predominately reddish or blue. It makes for muddy looking scenes, and in many cases the more common black & white film has stood up better over the years. This clip is stark, clear and the colors have survived the decades in remarkably good shape.

The morning of August 27, 1944 was a cold one (they all were) on Attu Island in the Aleutian chain. There on the edge of nowhere, Fleet Air Wing Four’s Lockheed PV-1 Ventura bombers carried on a fitful war against Japan’s northernmost bases in the Kurile Island group. Whenever the weather cooperated, the Ventura crews would sortie forth to hunt for shipping to bomb and land bases to attack.

Lt. Everett Price and his crew from VB-136 took off that morning just after 0700, bound for Otomari Zaki, one of the islands in the Kuriles. Price had orders to strike at any Japanese shipping encountered, or supplies discovered on the island there. It would be a long flight, and the Venture carried one thousand four hundred and fifty gallons of fuel to feed its twin Pratt & Whitney R-2800 radial engines.

At four thousand feet, Price tried to gauge the wind speed that day by looking down at the waves below. After studying the water, he concluded that the breeze was about half as intense as the 30 knots they had been told to expect earlier that morning. He told his navigator, Ensign George Campbell, to factor that change into his calculations. Not long after, Campbell fixed their position with a sunline and LORAN and he concluded they were 450 miles from their target area and about 175 minutes out. They were also off course to the north of their intended flight path. Campbell made some corrections and passed them to Price.

Later that morning, they spotted the Kamchatka Peninsula, watching it pass by on their starboard side. Flying in and out of clouds, they finally sighted a tall volcanic mountain that they thought was Araido To. A few minutes later, after four hours in the air, somebody called out two vessels off to starboard. Price made them out, perhaps twenty-five miles away. Towering clouds loomed in the distance to the south, and a fog bank hugged the wave tops near the two ships. They were close to the coastline of one of the Kurile Islands, which the aviators thought was Onekotan.

Price and his copilot, Ensign Francis Praete, banked the PV-1 toward the two vessels while the crew studied them with binoculars. One looked like a Japanese picket ship. The other was a tanker–a prime target for the Navy crews.

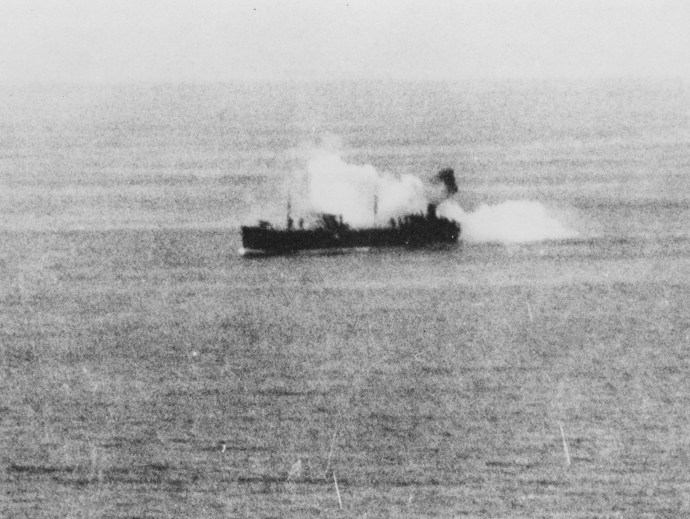

One of Gavin’s photographs that he shot with the K-20 while crouched between Price and Phaete. Here, the PV-1 crew is making their attack on the tanker.

Game on. Price pushed the yoke forward and dove to the attack. They dropped down to seventy-five feet and leveled off. The tanker seemed to be making about ten knots on a northeasterly course, and Price positioned the PV-1 for a beam attack.

Four thousand feet from the target, Price opened fire with the Ventura’s bow guns. He two second burst fell wide of the ship, chewing up the swells just forward of the tanker’s bow. He corrected, and hammered the vessel with a long, eight to ten second burst. The plane’s five .50 caliber machine guns spewed out about five hundred rounds, tearing through the bridge and superstructure, puncturing the hull and causing extensive damage.

Closing at 240 knots, Price kept firing, walking the nose back and forth with rudder inputs to try and suppress the anti-aircraft fire that was now directed against them. Several guns were located fore and aft on the tanker, and while they were not using tracers, the crew could see their muzzle flashes and feel near-misses buffet their aircraft.

This was the critical moment. Price remained laser-focused on executing their bomb run, Praete next to him on the controls as well. Between them crouched Paul Gavin, the radioman. He held a K-20 camera in hand and was shooting photographs of the attack.

The intercom suddenly lit up with chatter, but Price was so focused he couldn’t make out what was being said. Then Gavin suddenly pounded on his shoulder. Price ignored him. The tanker swelled before them, its masts well above the PV-1. One mistake now, and they’d careen into the ship and all be killed.

Lieutenant Price triggered the bomb release. Three bombs were supposed to fall out of the bay at hundred foot intervals. The first, an incendiary, failed to arm. The second, a 500lb General Purpose bomb, hung on the rack and failed drop. The third, another incendiary, released perfectly. It struck the tanker directly amidships and punctured a meter square hole in the hull about six feet above the waterline.

Price pulled up at the last possible moment, narrowly missing the tanker’s mast. As they cleared the area, Gavin snapped photos of the vessel burning, smoke boiling from the direct hit. It was a masterful masthead level bombing run, the sort perfected by the 5th Air Force, then passed on to the U.S. Navy’s bomber squadrons.

Except that the tanker was the Russian USSR Emba, a Suamico class fleet oiler built in Portland, Oregon. Completed in May 1944 she was handed over to the Russians as part of our Lend-Lease program at the end of June. The Russians had crewed it for only two months when Price’s crew put a hole in her hull.

Moment of impact. Price’s third bomb strikes Emba amidship. Emba survived the war and the Soviet Union turned her back over the United States in 1948. She was renamed Shawnee Trail, AO-142 and served through the 1960s in both the USN and the merchant fleet. She was sold for scrap in 1973.

It turned out that the chatter on the intercom during the bomb run came from the plane captain, Paul Knoop, who had spotted “USSR” written on the Emba’s side. Gavin also spotted Russian markings, which was why he started hitting Price’s shoulder.

When the PV-1 returned to Casco Field on Attu, Price found himself in the middle of an international incident. It turned out the crew had erred in their navigation and had wandered over the Russian sealane between the U.S. and Vladivostok. This sealane accounted for 50% of all the material sent by the United States to the Soviet Union during the war. Gasoline, oil, trucks, raw materials, railway cars and locomotives were all delivered via the Pacific Route. Armaments, aircraft, ammunition were all prohibited due to the touchy neutrality issues between Russia and Japan, so everything carried through Japanese waters had to be non-combat related.

An investigation commenced almost at once. A U.S. Navy inspection team examined the Emba on September 2, 1944, counting over a hundred and fifty bullet holes on the bridge alone. Other rounds pierced the hull and narrowly missed the ship’s doctor. Fortunately, the bomb hit did not compromise the Emba’s watertight integrity and caused no casualties.

Price and Phaete were disciplined for their mistake, though what that discipline was is lost to history now. Fleet Air Wing Four redoubled its ship identification efforts, and went over the recognition signal procedures with all air crew.

As the war ended in Europe and the air offensive against Japan became the focus of the USAAF’s last efforts in WWII, the B-17’s day as America’s work horse bomber came to an end. Most of the Forts still remaining in service with the 8th and 15th Air Forces would soon be scrapped or sent to bone yards. A few dodged that fate when the USAAF converted about 130 to perform a much needed and unheralded role in the Pacific.

The vast distances between targets in Japan and the B-29 bases in the Marianas assured that many crippled Superforts would end up in the Pacific.

Submarines were posted along the strike routes to help save the crews that went into the drink, but the USAAF needed their own Search And Rescue squadrons to help find those men. A number of air rescue squadrons were already in service in the Pacific, mainly flying the venerable PBY Catalina. In the final months of the war, the USAAF began employing modified Forts in the SAR role.

Submarines were posted along the strike routes to help save the crews that went into the drink, but the USAAF needed their own Search And Rescue squadrons to help find those men. A number of air rescue squadrons were already in service in the Pacific, mainly flying the venerable PBY Catalina. In the final months of the war, the USAAF began employing modified Forts in the SAR role.

Dubbed the B-17H “Flying Dutchmen,” the planes carried an A-1 Higgins lifeboat under the fuselage. Twenty-seven feet long, self-bailing and self-righting, these boats could be dropped by the Forts to downed crews bobbing on the Pacific swells. Three parachutes would deploy and help ensure the boat landed in the water safely. Once aboard, the wet airmen would find blankets, provisions and survival gear waiting for them, all carefully stowed in the A-1.

The Flying Dutchmen also carried search radars in place of chin turrets. Operating from Ie Shima Island in the final weeks of the war, the Flying Dutchmen of the 5th Air Rescue Group saved a number of B-29 crews before the Japanese surrender. They continued in USAAF and USAF service, performing their vital duties in the Korean War and beyond until 1956. After 1948, they were redesignated SB-17G’s.

Professor Edward Mooney has shared a link that shows how the Higgins Boat was deployed. Thank you Dr. Mooney!

http://members.peak.org/~mikey/746/boat.htm

The Japanese did not oppose the American landing at Amchitka in January 1943, though the rough waters and dangerous shoals around the island claimed the USS Worden (DD-352). Fourteen of her crew died as their ship broke apart and sank on the rocks.

Amchitka was easily one of the most remote and inhospitable U.S. military outposts of World War II. It was so remote that during the Cold War, the U.S. detonated three nuclear warheads on the island in various underground tests. Located about 80 miles from Kiska Island in the Aleutian chain, American forces landed there unopposed in January 1943 and quickly built an airfield there to support the final stages of the campaign in the far north. Once the Japanese had been driven from Attu and Kiska, Amchitka-based Navy patrol bombers and 11th AF aircraft began periodic attacks on the Japanese Kurile Islands.

It was a dreary place to be stationed. The weather was awful, accidents frequent, mud or frozen snowdrifts the polarities of daily living. Yet, the men exiled to Amchitka did their best to make the place home. This included their own version of an American tradition–the Thanksgiving Day football game.

In early May of 1945, Ensign Tom Binford, a U.S. Navy photographer, arrived on Okinawa after spending part of the previous months snapping pics of seaplane tenders around the Marianas. He embedded with VPB-118, one of the USN’s patrol bomber squadrons that had just reached the island, where the crews would soon be flying long range anti-ship missions over the Sea of Japan and the Yellow Sea.

Binford was a masterful photographer, and his photos documenting the preparations for one of those missions are both dramatic and artistic. The compositions are especially striking.

VPB-118 was commissioned in July, 1944 outside of San Diego. The crews flew practice bombing missions around San Francisco throughout the fall of 1944. (Can you imagine the Navy doing that today? Holy smokes!). In late ’44, the squadron shipped out and arrived on Tinian to join Fleet Air Wing 1, flying its first mission in January 1945. On April 22nd, VPB-118 moved to Yontan Airfield on Okinawa while fighting still raged on the island.

Shortly after Binford took these photos, one of the squadron’s PB4Y Privateer bombers went missing somewhere on patrol. The crew lost included:

Lt. J.A. Lasater

Ens. M.L. Gibson

Ens. C.J. Milner

AMM2c E.W. Smith

ARM3c W.J. Hawkins

AMM3c C.W. Jacobs

AOM2c R.E. Miller

AMM2c S.C. Bryant

ARM3c D. McAllsiter

ARM3c H.F. Brockhorst

AOM3c W.L. Thornton

AMM3c R.A. Carr

Altogether, the “Old Crows,” as the squadron named itself, lost thirty-one men killed or missing in action.

1st Marine Division M5 Stuart light tank crew taking a short break during the brutal fighting at Cape Gloucester, New Britain. January 16, 1944.

During the final months of the Pacific War, MacArthur tasked the Eighth Army under Lt. General Robert Eichelberger with liberating the Central Philippines. The 40th Infantry Division, a National Guard unit from California, Nevada and Utah, played a key role in this all but forgotten campaign. In March 1945, the “Sunshine Division” landed on Panay, encountering stiff resistance in places during a ten day battle to clear the island.

On the first day of the landing, March 18th, two Signal Corps photographers followed an infantry company from the 185th Infantry Regiment ashore to photograph the fighting and their advance. A company of M4 Sherman tanks spearheaded the push into Panay’s jungle interior, and the men of Alpha Company, 1st Battalion, 185th Infantry followed cautiously behind. The photographers, Lt. Robert Fields and T/5 Howard Klawitter, ignored Japanese incoming machine gun and light artillery fire and stayed right with the GI’s of Alpha Company, snapping photos as they dashed forward with them.

As the combined force pushed up along a dirt road, they encountered heavy resistance and Alpha Company took cover behind the tanks. The Shermans blasted away at the Japanese defenders while Fields and Klawitter, standing a few yards apart, snapped pictures of the firefight.

Both photographers went down within minutes of each other. Fields was killed and Klawitter wounded. These two photos are the last ones they took.

Howard Klawitter’s final photo before he was wounded in action while attached to Alpha Company, 185 Infantry, 40th Infantry Division, California National Guard.

This is the last photo taken by Signal Corps photographer Lt. Robert Fields. We was killed by incoming Japanese fire moments later. His camera was recovered and the film developed. He’d snapped four photos on the roll before his death while chronicling Alpha Company, 1st Battalion, 185th Infantry.