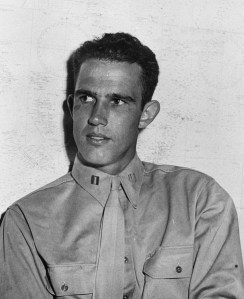

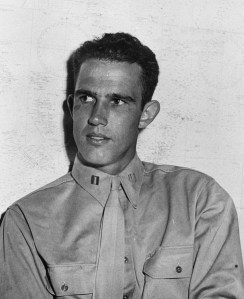

Marion Carl grew up in the tiny village of Hubbard, Oregon, a few dozen miles southwest of Portland. After graduating from high school, he enrolled at Oregon State University. While studying engineering, he also joined the Corps of Engineers and ROTC. In the fall of 1937, during his senior year, Carl learned to fly on a Piper J-2 Cub at an airport just outside of Corvallis. In May, 1938, Carl went up to Fort Lewis, Washington tried to enlist in the Army Air Corps . The Air Corps turned him down, citing unspecified physical reasons. Later, Carl discovered that the recruiter had filled his quota for the month and had rejected him for that reason.

Marion Carl grew up in the tiny village of Hubbard, Oregon, a few dozen miles southwest of Portland. After graduating from high school, he enrolled at Oregon State University. While studying engineering, he also joined the Corps of Engineers and ROTC. In the fall of 1937, during his senior year, Carl learned to fly on a Piper J-2 Cub at an airport just outside of Corvallis. In May, 1938, Carl went up to Fort Lewis, Washington tried to enlist in the Army Air Corps . The Air Corps turned him down, citing unspecified physical reasons. Later, Carl discovered that the recruiter had filled his quota for the month and had rejected him for that reason.

He graduated from OSU in June, 1938 and spent the summer up at Fort Lewis as a second lieutenant in the Army. Despite the Air Corps’ reject, Marion was determined to find a way into the air. He went to see a Navy recruiter and was accepted into the naval aviation cadet program. In August, he reported for duty in the Navy. In one day, he went from a second lieutenant in the Army to a Seaman Second Class in the Navy to a Private First Class in the Marine Corps! Years later, Marion Carl would become one of the rarest of officers–one who worked his way up from private to general in the course of a most distinguished military career.

Carl recalled in a 1992 interview that he chose the Marine Corps for two reasons, “I wasn’t all that enthusiastic about being at sea so much. The other was, of the eight of us there, I was the only one who qualified for the Corps. I was the only one with a college degree. The Navy was taking men with two years, but the Marines weren’t. You had to have a college degree. On top of that, I got to Pensacola a month ahead of the others.”

Of the eight other young men Carl joined up with that summer, three washed out of flight school. The other five became Navy pilots.

When the war began, Carl was serving with VMF-221, a fighter squadron equipped with the squat, barrel-shaped Brewster F2A Buffalo. Just after Pearl Harbor, Carl and the squadron boarded the U.S.S. Saratoga as part of the Wake Island relief expedition. VMF-221 was supposed to be launched from the Saratoga, fly to Wake and help defend the atoll with the remnants of VMF-211, the Wildcat squadron already there.

Just before the Saratoga came into range of Wake, the operation was canceled. The frustration the Marines felt was palpable, and on the bridge of the Sara, officers talked openly of disregarding these orders. Nevertheless, the task force turned around and aborted their mission. A short time later, the gallant defenders of Wake Island surrendered to overwhelming Japanese forces.

Instead of going to Wake, Marion Carl and VMF-221 went to Midway Atoll. There, amongst the gooney birds, the men wallowed in boredom for nearly six months, flying training missions but never sighting the Japanese.

Midway Atoll. This is Sand Island.

At the end of May, 1942, Midway received a sudden influx of reinforcements. They came in drips and dribbles– a few B-17s, a quartet of Marauders from the 22nd Bomb Group, and six TBF Avengers from Torpedo Eight. Having broken the Japanese naval code, JN-25, the Americans knew the Japanese would soon be attacking Midway. Every available airplane was rushed to the Atoll.

That attack came on the morning of June 4, 1942. VMF-221 took to the air in defense of Wake Atoll. Carl took off with the squadron flying a Grumman F4F Wildcat, one of six the squadron now possessed. Together with the Buffalos, the Marines were able to put up twenty-five fighters to meet over a hundred Japanese aircraft, all flown by crack veterans of the China Incident, Pearl Harbor and the Ceylon Raid. The result was a slaughter. The Zeroes flying cover for the Nakajima B5N Kates and Aichi D3A Vals had placed themselves too high and too far behind their chargees to prevent the Marines from making one unhindered pass. The Americans took advantage of the mistake and managed to claw down a couple of bombers before the Zeroes descended upon them in all their fury. The Brewsters, unmaneuverable and slow, were chopped to pieces by the expert Japanese pilots.

One of the surviving F4F-3 Wildcats at Midway, seen after the battle.

Marine Carl not only held his own, he damaged a bomber before the Zeroes swarmed all over his division. Climbing out of the fight, he went looking for trouble at 20,000 feet. In 1992, he recalled to me, “The next thing I knew, I had a Zero on my tail. I didn’t know he was there until these tracers started going by. I racked it into a tightest turn I could. He followed me and made it look easy! So, I headed for the nearest cloud. He hit me eight times.”

Just inside the cloud, Marion cut his throttle and skidded the Wildcat. When he popped out the other side, he caught sight of the Zero scuttling along below. Marion shoved the stick forward and opened fire at the same time. The sudden dive jammed all his guns, allowing the Zero to escape.

After clearing three of his guns, he returned to Midway to discover a trio of Zeroes lagging behind the rest of the strike group. Carl followed the three Japanese fighters, waiting for his opportunity to strike. Finally, as one of the three Zeroes began falling behind the others, the Oregonian attacked. He dove down behind the Zero and opened fire from dead astern. The Mitsubishi crashed into the water off the reef that surrounded the atoll.

It was the first of eighteen kills Marion Carl would claim in two years of combat.

When he returned to Midway, he discovered that fully half his squadron had been killed in the fight. In fact, besides his own Wildcat, only one other fighter was operational. It was a grim introduction to combat.

Two months later, Carl and VMF-223, his new unit, landed at Henderson Field on Guadalcanal. Throughout August and September, the gritty Marines fought a desperate battle of attrition in their daily encounters with the Japanese. On August 24, 1942, in the middle of the Battle of Eastern Solomons, Carl and his division intercepted an inbound strike from the Japanese carrier Ryujo. In the dogfight that followed, the young Oregonian gained credit for downing two Zeroes and two B5N Kates, making him the first U.S. Marine Corps ace.

Only a few weeks later, the hunter became the hunted.

Henderson Field, Guadalcanal seen August 22, 1942.

An F4F scrambles at Henderson Field.

September 9, 1942 was a typical day for the beleaguered American Marines on Guadalcanal. Shortly after 11:00, Australian coastwatchers reported a major Japanese raid headed for Henderson Field (code-named Cactus), the airfield the Marines were doggedly trying to defend. Cactus Control ordered a full-scale scramble as soon as it received news of the impending attack. The pilots of VMF-223 and -224 raced to their fighters, which had been warmed up and ready to go since dawn. Captain Marion E. Carl was one of the sixteen Wildcat pilots in the cockpit that day. He climbed into his F4F-4, strapped in, and taxied out of the dispersal area. With his stubby fighter now on the runway, he opened the throttle. The Wildcat careened down Henderson Field and bounded into the cloudy skies above Guadalcanal. After Carl took off, one pilot from VMF-224 did not quite make it. He stalled just as he got airborne, and his Wildcat smacked into the ground at the end of the runway. Now there were fifteen Grummans to meet the Japanese attack.

John L. Smith, Bob Galer (Medal of Honor) and Marion Carl at Guadalcanal.

Though Carl had only been on the island since August 20th, he had already carved a niche for himself in aviation history. Six days after arriving at Henderson Field he had shot down his fifth Japanese plane. In doing so, he became the first U.S. Marine to ever reach acehood. He had continued to add to his score, and only his squadron’s commander, John L. Smith, had any chance of catching his tally. Smith and Carl enjoyed a friendly rivalry, each one determined to leave Guadalcanal with the laurels of top ace status. Carl to this point had remained comfortably in the lead, but the September 9th mission would alter the balance between the two aces.

The Wildcats pointed northward and labored for altitude. For once the Marines had received enough warning to climb above the Japanese bombers. Often, word of an impending attack came too late for the F4F’s to get to a proper intercept altitude. The frustrated pilots would watch the Mitsubishi G4M Betties pass serenely overhead while their Wildcats struggled for altitude thousands of feet below. This time, though, the Marines managed to get to about 23,000 feet before the noontime raid arrived. The raid consisted of two formations; one Vee of G4Ms, and another of escorting A6M2 Zekes. The Zekes trailed behind the bombers, keeping watch over their charges as they shepherded them to the target area.

A formation of G4M Betty bombers seen later in the war at Okinawa. This is a still image from gun camera film taken by an F6F Hellcat belonging to VF-17.

On this day, the Marines had the altitude advantage. Like the intercept over Midway, the escorting Zekes were again caught slightly out of position. Carl led his men to a point about a mile ahead and off to one side of the Vee of Betties. In column formation, the Marines executed 180 degree turns and dropped down on the bombers. With his nose pointed almost vertical, Marion’s Wildcat accelerated to over four hundred miles per hour. He had just enough time to give a Betty a long burst from his six fifty caliber machine guns as his Wildcat howled through the formation. The fifties stitched the bomber from nose to tail, tearing apart the crew positions. It fell earthward, mortally wounded.

Engine roaring, Carl swept under the stricken plane, ready to make another attack on the formation. Using the speed he had gained during his first pass, he zoomed back up above the Japanese and turned to make another overhead run on them. Down he went again, his Wildcat whining furiously as he pushed the nose towards the vertical again. Guns chattered, tracers flew. Another Betty dropped out of the formation, victimized by the sharpshooting Oregonian, its engines coughing up great spumes of smoke.

Engine roaring, Carl swept under the stricken plane, ready to make another attack on the formation. Using the speed he had gained during his first pass, he zoomed back up above the Japanese and turned to make another overhead run on them. Down he went again, his Wildcat whining furiously as he pushed the nose towards the vertical again. Guns chattered, tracers flew. Another Betty dropped out of the formation, victimized by the sharpshooting Oregonian, its engines coughing up great spumes of smoke.

Then, Marion got reckless.

Another gun camera still from VF-17’s Okinawa dogfight. This Betty was carrying a rocket-powered suicide stand-off bomb called a Yokosuka MXY7 Ohka. It is just visible under the Betty’s centerline.

Carl had limited himself to only one or two passes at the bombers on his previous intercept missions. After two runs, the Japanese fighter escort usually had enough time to intervene. After his second pass, he would roll inverted and dive for the deck. No Zero could keep up with a Wildcat in a steep dive above 10,000 feet, so the maneuver ensured he would make it back to Henderson to fight another day.

On September 9th, Carl saw no Zeroes, heard no warning calls. He decided to attack the bombers one more time. He climbed back over the Betties, selected one and rolled in on his target.

As he started his run, his F4F suddenly shuddered. Cannon and machine gun strikes rocked the Wildcat, and Carl had no chance to react. A Zero had somehow slipped behind him. In seconds, Carl’s engine exploded in flames. Smoke poured into the cockpit, stinging his eyes and disorienting him. The smoke forced him to open the canopy, which added such drag to the Wildcat that Carl knew he was now a “dead pigeon” for the Japanese pilot behind him.

With the smoke came an intense wave of heat. Later he would recall, “The one way I didn’t want to go was to get burnt, to get fried. I don’t take long to make up my mind on something like that. So I just rolled the [Wildcat] over and out I went.”

Carl had bailed out at about 20,000 feet. By the time his parachute opened, the air battle had passed him by. Not a single aircraft remained in sight. He spiraled downwards in his chute, enjoying a birds-eye view of Guadalcanal and its environs. He landed in the water about a mile off shore.

For several hours, he floated in his Mae West, treading water and trying to prevent the current from dragging him away from shore. He kept his flying shoes on, and held onto his Colt .45, figuring he’d need them when he got ashore. Still, the weight of these burdens tired him out, and he began to lose headway against the current. Before he had bailed out, his face had been slightly burned by the heat in the cockpit, and the wound began to ache.

A Marine patrol on Guadalcanal in the fall of 1942. After Carl ended up in the water, he faced a challenging trip to get back through Japanese lines to reach the Marine perimeter around Henderson Field.

Fours hours later, a native canoe cut through the choppy waves towards him. Exalted that help had arrived, Carl began to shout out, “American! American! American!” The native wasn’t completely convinced, however, and circled the downed aviator for several minutes before concluding he indeed was an American. He helped Marion climb into the canoe, introduced himself as Stephen, then began to paddle towards shore. He brought Carl to a small native encampment, where he was introduced to a native from Fiji who had been serving as a doctor for the local inhabitants. Corporal Eroni spoke good English, and proved more than willing to help the American get back to Henderson Field.

After trying unsuccessfully to get back to the perimeter overland, Carl and Eroni decided to go by sea in an eighteen foot skiff. The small boat was powered by an ancient single cylinder engine which at the moment did not work. Fortunately the resourceful Marine had plenty of experience with small engines, as he had purchased a scooter some months before that had demanded constant mechanical attention. He managed to get the skiff’s engine working after tinkering with it for most of an evening.

That morning, around 4:00 A.M., Carl, Eroni and two other natives set out for Henderson Field. The boat weaved its way along the coast, the two men keeping a sharp watch for any Japanese troops. By 0700, they had reached Lunga Point, where the Oregon Marine splashed ashore to report back for duty.

When Brigadier General Roy Geiger, the commander of the air striking force on Guadalcanal, heard of Marion’s return, he sent for the intrepid Marine immediately. Moments later, Carl stood before him, saluting happily. The two men chatted amiably for a while, then Geiger mentioned that Smith had just shot down his sixteenth plane. With the two Betties he got on the ninth, Carl had only twelve. “What are we going to do about that?” demanded Geiger playfully.

John L. Smith, Dick Mangrum and Marion Carl.

“Goddamnit General, ground Smitty for five days!” Carl replied.

Smith finished the war with 19 kills and the Congressional Medal of Honor. Carl ended his WWII combat career with 18.5 victories.

Word spread quickly throughout VMF-223 that Carl had returned. His comrades were overjoyed to see him, though some were also a little embarrassed. After he went missing, the pilots figured he was gone for good and divided up his possessions. Marion had to spend the day rounding up his personal belongings. Finally, he managed to recover his scooter, his short wave radio and all his other nick-knacks except for a pair of shower shoes. He had kept them carefully under his cot, his name carefully marked on their soles in black, indelible ink. Carl searched high and low, but found no trace of them.

In the late 1950’s Carl was stationed in Headquarters, Marine Corps in Washington D.C. as part of the Commandant’s staff. He’d become a colonel by then and was on track to get his brigadier’s star.

One day, the Marine Corps Commandant, General David M. Shoup, took him aside after a meeting and said to him, “By the way, Marion, I’ve gotta pair of shoes of yours.”

A Marine dug out at Henderson Field.

Puzzled, the Oregonian asked, “What do you mean you’ve got a pair of my shoes?”

Shoup explained that he’d been serving with a Marine line unit defending Henderson Field that fall. After Marion had gone missing in action, Japanese warships shelled the Marine perimeter. The onslaught had flatted Shoup’s quarters, along with many other tents and structures around the airfield. After the Japanese ships steamed back up the slot, Shoup crawled out of his foxhole and went looking for a place to sleep. He came across Carl’s tent, learned that the Oregonian had been posted missing, and decided to curl up on his cot. In the morning, as he headed back to his regiment, he caught sight of the shower shoes under the cot. He scooped them up, figuring a dead man didn’t need them, and disappeared.

Shoup finished his tale by telling Carl he wasn’t going to give them back. “They’re the luckiest pair of shoes I’ve ever had,” he told Carl. “I credit them for keeping me alive during the war.”

Betio Island, Tarawa, November 1943.

They must have been truly lucky shoes. Shoup carried them in his pack when he hit Beach Red at Betio with the first Marine waves in November, 1943. In the first desperate hours of the invasion, he took command of the Marines clinging to the waterline and led the push inland. His actions that day earned him a Medal of Honor. Later, though assigned as a divisional staff officer, he found his way to the front lines during the Battle of Saipan, where he was trapped in a forward observer’s position for several hours. He later received a Legion of Merit for his role in the Marianas campaign.

David Shoup, with his family looking on, receives the Medal of Honor at the Navy Department in Washington D.C. on January 22, 1945.

Marion Carl stayed in the Corps after the Japanese surrender. As a Marine test pilot, he earned numerous “firsts” in his illustrious career. Besides being the first Marine ace, he was the first pilot in the Corps to land a jet fighter on an aircraft carrier, and he set a world’s speed record in 1947, going 650.6 mph in a Douglas Skystreak. Later, he commanded the first jet aerobatics team, was the first military pilot to wear a full pressure suit and in 1986, he became the first living Marine to be enshrined in the Naval Aviation Hall of Honor. Brigadier General Marion Carl retired on June 1, 1973, with over 14,000 hours in some 250 different plane types, ranging from experimental rocket propelled aircraft to canvas-covered puddle jumpers. In the course of his thirty-four year career, he earned two Navy Crosses, five DFCs, four Legions of Merit, and fourteen Air Medals. Not bad for a small town farm kid.

In June of 1998, a 19 year old drug addict broke into Marion’s ranch house east of Roseburg, Oregon. Wielding a shotgun, the intruder wounded Marion’s wife, Edna, with a blast of gunfire. Hearing the racket, Carl burst out of his bedroom and flung himself in front of his wife, just as the addict pulled the trigger again. Carl was killed instantly. He died as he had lived—a true hero whose measure lay not in his many accomplishments, but rather in the size of his enormous heart.

Val C. Pope served with a U.S. Army Signal Corps company during World War II. He was one of the first combat cameramen to make it ashore on D-Day. He landed on Omaha Beach with still photographer Walter Rosenblum sometime during the morning of June 6th. Armed only with a movie camera, Val and Walter set about capturing the chaos on Omaha as it unfolded around them. One of the most gripping movie clips Val shot that survived the landing was the rescue of several drowning GI’s. Their landing craft was hit and sinking, and as they ended up in the water floundering, a young lieutenant saw their plight from shore. He grabbed a cast away life raft, jumped into the surf and swam out to them. Val’s footage shows the men being helped ashore.

Val C. Pope served with a U.S. Army Signal Corps company during World War II. He was one of the first combat cameramen to make it ashore on D-Day. He landed on Omaha Beach with still photographer Walter Rosenblum sometime during the morning of June 6th. Armed only with a movie camera, Val and Walter set about capturing the chaos on Omaha as it unfolded around them. One of the most gripping movie clips Val shot that survived the landing was the rescue of several drowning GI’s. Their landing craft was hit and sinking, and as they ended up in the water floundering, a young lieutenant saw their plight from shore. He grabbed a cast away life raft, jumped into the surf and swam out to them. Val’s footage shows the men being helped ashore.

It was 1930 hours, December 20, 1944. Christmas season in Belgium’s Ardennes Forest. The 82nd Airborne reached the battlefield only two days before after a wild drive up from France. Thrown into the path of Kampfgruppe Peiper, the men of the 82nd had no time to get oriented, lacked winter clothing and carried nothing heavier than bazooka rocket launchers.

It was 1930 hours, December 20, 1944. Christmas season in Belgium’s Ardennes Forest. The 82nd Airborne reached the battlefield only two days before after a wild drive up from France. Thrown into the path of Kampfgruppe Peiper, the men of the 82nd had no time to get oriented, lacked winter clothing and carried nothing heavier than bazooka rocket launchers.