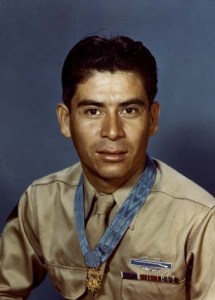

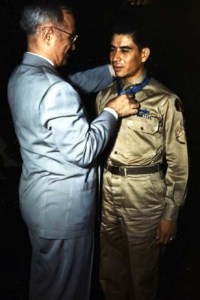

Colonel Gerald R. Johnson, who finished the war with 22 confirmed air-to-air victories.

Colonel Gerald Johnson and the Napalm Attacks in the Philippines

The 1945 Battle for Luzon is often remembered solely by the drive from the beaches at Lingayen Gulf to the Battle of Manila, with daring special operations and air assaults conducted to rescue American civilian internees and prisoners of war.

Men of the 37th Infantry Division crew an anti-tank gun in the house-to-house fighting in Manila, February 1945.

There is no finer work written on the tragic Battle of Manila than James Scott’s Rampage. This book is a telling, deeply emotional and vivid description of the house-to-house fighting and senseless mass murders that defined the battle. It is not an easy read, but one that provides critical insight into the mindset of American leaders in the Western Pacific during the final months of the war. Scott’s book is a sober reminder that the cost of liberation sometimes came at an unbearable price for those who sought to liberate.

Yet, even after the fall of Manila, there was considerable fighting left to be done elsewhere on Luzon. Hundreds of thousands of Japanese troops, well-organized and deeply entrenched, had retreated into the mountainous terrain northwest of Manila and were determined to make the FilAmerican forces pay for every inch of ground they captured.

From the end of February to the end of May, the bulk of both the U.S. Eighth and Sixth Armies battered there way forward toward several key objectives: Baguio, the Philippine summer capital, the mountain passes from Central Luzon into the Cagayan Valley, and the dams that provided Manila’s water supply.

The Japanese resisted with ferocious desperation. In countless small actions, they died to the last man. We Americans remember the Alamo, Wake Island, the 20th Maine’s stand at Gettysburg and the 1st Minnesota’s suicidal charge on the second day of that battle. What is exceptional in American military history was routine for the Japanese Imperial Army. During the fighting for these three objectives, they proved their nihilistic courage time after time. That willingness to fight to the last bullet and breath combined with the Imperial Army’s broad and relentless brutality toward civilian and captured American servicemen made the Japanese a truly terrifying foe.

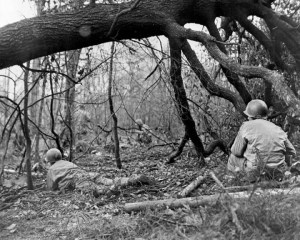

Men of the 25th Infantry Division fighting on a ridge near Baguio in April 1945. The next month, the 25th would see fierce fighting at the Cagayan passes.

From the end of February through April and May, the two U.S. Armies hammered their way forward through pouring rain that turned the few roads to rivers of mud. The Japanese made the Allies pay for every ridge they seized, and the fighting bogged down to a World War I-esque battle of attrition.

The terrain over which the 33rd Infantry Division had to advance to assault Baguio.

In April, on the Eighth Army’s front, the 33rd Infantry Division struggled forward to liberate Baguio. They faced formidable defenses built around ridges, hilltops and a river line. The Japanese dug in deep, bored tunnels in the mountain sides, carefully concealed artillery pieces that could be pulled back into deep caves after a fire mission.

US Army map of the 33rd Infantry Division’s fight to liberate Baguio.

With the Japanese Army Air Force and Naval Air Force destroyed in the Philippines, the U.S. possessed complete command of the air over Luzon. The ground troops turned to the aviators for help in breaking the Japanese resistance.

Cockpit view of a P-38 dive bombing mission near Baguio.

Thousands of ground attack missions were carried out against specific targets, sometimes only a few hundred yards from the forward most FilAmerican troops. The P-38 pilots in the V Fighter Command went from flying for months against Japanese bombers and interceptors, to finding themselves carrying out close air support strikes. There was no glamour here, no press, no racking up of victories that could be glued to the sides of their P-38s. It was difficult, dangerous low-altitude work that required great skill and coordination to do without killing friendly troops.

Those grinding, daily dive-bombing and strafing missions became a vital source of support for the ground troops. The few Japanese who were captured stated they feared the fighter-bombers more than they feared American artillery bombardment. Why?

Napalm.

A 25th Infantry Division squad under fire near Baguio, April 1945.

In mid-April, on the 33rd Infantry Division’s front, the 130th Infantry Regiment called for air support to help the rifle companies get through a network of fortified hills overlooking a river. The theater’s highest scoring fighter groups—the 49th and 475th— answered the call along with several others. For days, the fighter-bombers drenched the Japanese defenses with napalm and five hundred pound bombs. In one attack carried out by the 49th Fighter Group, a tunnel was hit with napalm, killing two hundred Japanese soldiers.

These attacks broke the back of the Japanese resistance. The 130th got across the river and the 33rd Infantry Division liberated Baguio’s ruins on April 26, 1945. It was a remarkable display of air-ground cooperation, and it set the table for larger operations in the weeks ahead.

Though ordered out of combat by General Kenney, Johnson continued to fly ground attack missions with his 49th Fighter Group all the way up until July 1945 when he was promoted to a staff job within Fifth Air Force HQ. There he helped plan the air component of the invasion of Southern Japan.

Flying with the 49th during many of these attacks in support of the 130th was quadruple ace Gerald R. Johnson. Johnson and Charles MacDonald of the 475th Fighter Group were the two leading aces still active in the SWPA by this point of the war. McGuire was dead, Kearby was dead and Bong was back home about to join the P-80 Shooting Star program.

Far Eastern Air Forces commander, General George Kenney, specifically ordered 5th Air Force commander Ennis Whitehead to pull Johnson out of combat to save him for the post-war era. He was looking down the road and knew the USAAF would need a crop of brilliant leaders to gain independence from the Army and secure the primacy of American airpower in any future war.

George Laven, Gerald Johnson, Clay Tice standing. Bob DeHaven, Wally Jordan, Jim Watkins in front row. The photo was taken a month after the mass napalm raids. Watkins, Jordan and DeHaven were all aces along with Gerald.

Johnson was not having any of it. At twenty-four, he was a full colonel and in command of the 49th Fighter Group. He refused to let his men do the difficult flying without him. Through April, he flew against the Japanese defenses around Baguio, sometimes two missions a day. He coordinated many of the strikes from the air, communicating with the forward air controllers on the ground to get the bombs and napalm where they needed to go.

When the fighting ended and Baguio was liberated, the commander of the 130th Infantry, Colonel Arthur Collins, wrote a detailed letter to Gerald Johnson thanking him and his pilots for their skill and destructiveness.

The ruins of Baguio, April 1945.

The following month, two major battles culminated almost simultaneously. In the Sixth Army sector, the 43rd Infantry Division was trying to take the Ipo Dam from a Japanese force that included three regiments and multiple additional battalions. The force defending the dam totaled over seven thousand men. The 43rd’s advance was slowed by the fierce Japanese resistance.

The Ipo Dam was one of two that controlled the water supply into Manila. Capturing them from the Japanese became a top priority after the fall of the Philippine capital.

This time, V Fighter Command worked out a new type of attack to break the Japanese hold on the dam. Instead of going in as flights or squadrons, the fighter-bombers would go in as entire groups in one, rolling hammer-blow designed to drench five key defensive positions with massive quantities of napalm.

US Army map of the Ipo Dam operation showing the 43rd and 38th Infantry Division’s boundary and area of operation.

On the morning of May 17, 1945, Johnson gathered his pilots and briefed them. He was excited and exuberant—one of his pilots later described him as sounding like a high school cheerleader (he was a yell leader at Eugene High, so that fit). As a final word to his men, the great ace declared, “We’re going in wingtip to wingtip, wave after wave!” he then led the 49th into the fight.

Johnson ,at left, leading the 49th on the May 17, 1945 Ipo Dam attack.

They saddled up and flew the mission—along with two hundred other fighter-bombers. The squadrons dove down into the valley around the Ipo Dam in tight, line abreast formations, driving through clouds of smoke boiling up from the preceding attacks, and delivered their deadly ordnance on their targets.

A P-38 (at left) makes a run over a hilltop defensive network near the Ipo Dam during the May 17, 1945 raid.

The mass attack by V Fighter Command left the Japanese defenses in a shambles. Almost seven hundred Japanese were killed outright—ten percent of the total number holding the dam. Dozens of vehicles, guns, supply and fuel dumps were incinerated by the blankets of napalm. Of those Japanese who survived, many panicked and fled the slicks of fire immolating their fighting positions. When V Fighter Command learned this, future attacks included a wave of light bombers dropping parafrags to kill those men as they fled.

The 43rd’s assault carried through the areas devastated by the napalm raids and quickly seized the dam. An unusual number of Japanese were captured, most dazed by the aerial onslaught. They were quickly interrogated to determine the effectiveness of the napalm strikes, and the POW’s offered a few insights:

Captured Japanese at the Ipo Dam, under guard by men of the the 43rd Infantry Division.

Another photograph of the POW’s taken at the end of the Ipo Dam fight.

This novel attack tactic was duplicated a few days later on the Eighth Army’s front where the 32nd and 25th Infantry Divisions were locked in a terrible fight along the Villa Verde Trail and Highway Five some ninety miles north of the Ipo Dam. The line of advance to seize the two vital passes into the Cagayan Valley was exceptionally narrow, supplied by twisting, winding roads turned to bogs by the incessant rain. The two American divisions faced two intact Japanese divisions, one of which was an armored unit. Yard by yard, the fighting here had raged since February 21st, and the Japanese were taking a terrible toll of the Americans. Ultimately, it would cost some seven thousand American and Filipinos to clear the mountains and open the passes.

To support the final assaults on the passes, V Fighter Command assigned four groups to carryout rolling mass napalm attacks on the Japanese 10th Infantry Division. For two days, Gerald Johnson led the 49th against these defenses at the Balete Pass. The defenders were smothered in flaming napalm. Following the 49th’s attacks came waves of fighter-bombers from the 475th, 8th and 58th Fighter Groups to add to the carnage on the ground. Artillery pieces were burnt in place. Dugouts and bunkers and caves were turned to charnel houses. Stunned Japanese survivors emerged from their entrenchments to flee the fires, only to be cut down by parafrags dropped by A-20s of the 312th Bomb Group.

P-47 Thunderbolts, probably from the 58th Fighter Group, coming off target during the mass attack on the Japanese defenses around the Ipo Dam.

Both passes were captured shortly after these attacks. Some thirteen thousand Japanese died in the fighting there.

Men of the 32nd Infantry Division advance up the Villa Verde Trail en route to the Cagayaan Valley passes.

Fighter pilots generally hated ground attack missions, preferring instead to be out hunting in the clouds. Shooting Japanese planes down made the headlines, but these mass napalm attacks saved the lives of countless American GI’s struggling forward in the worst imaginable conditions.

For Gerald Johnson, that was one of his most meaningful accomplishments. In New Guinea and on Leyte, he’d seen first hand how the infantry lived and fought. He felt tremendous respect for them, and knew his lot in the war was much easier than what they faced.

One night, after losing a close friend, Gerald sat down and wrote of that respect to his father:

“Our men are fighting the most difficult battles of the war… Men are wounded or killed. Husbands, fathers. Brothers and sons are giving their last full measure, Dad. There are no braver or courageous men anywhere than these thousands of unsung heroes who are defeating the Jap[anese].

A few of us get the medals and become “heroes” yet we live well and have a fighting occupation that suits our stomachs.

Every time I started to complain, I think how selfish, how little I am. Those men lie awake in a stinking water-filled foxhole, waiting for a rustle of a Jap[anise] crawling on his belly. Those men who crawl out of the mud in the midst of a lead filled morning to find their buddy next to them is dead, his throat slit because he was too sleepy and exhausted to maintain constant vigilance—they are the real heroes dad.”

A heavy weapons squad from the 25th Infantry Division at the Balete Pass.

Notes:

The American troops on the ground sent messages of thanks to the fighter groups involved in these attacks:

The 130th Infantry Regiment’s commander, Colonel Collins, sent this to Colonel Gerald Johnson:

This was sent by the commanding general of I Corps, which carried out the assault on the Ipo Dam. General Swift apparently witnessed the subsequent mass napalm strike on the Eighth Army’s Front at the Balete Pass a week after the dam was captured.

This was sent by the commanding general of I Corps, which carried out the assault on the Ipo Dam. General Swift apparently witnessed the subsequent mass napalm strike on the Eighth Army’s Front at the Balete Pass a week after the dam was captured.

For more on Gerald Johnson, the ace race and the fighting in the Southwest Pacific Theater, please see our upcoming book, Race of Aces, due out on January 14, 2020!

This was sent by the commanding general of I Corps, which carried out the assault on the Ipo Dam. General Swift apparently witnessed the subsequent mass napalm strike on the Eighth Army’s Front at the Balete Pass a week after the dam was captured.

This was sent by the commanding general of I Corps, which carried out the assault on the Ipo Dam. General Swift apparently witnessed the subsequent mass napalm strike on the Eighth Army’s Front at the Balete Pass a week after the dam was captured.

For one weekend every year since 1957, the skies over Chino, California fill with the sights and sounds of World War II aircraft. Nestled on an old Army Air Force base where the likes of 24 kill ace Gerald R. Johnson once trained, hosts this incredible event as one of its main fund raisers. These days, lucky visitors to Chino can see upwards of forty warbirds thunder overhead.

For one weekend every year since 1957, the skies over Chino, California fill with the sights and sounds of World War II aircraft. Nestled on an old Army Air Force base where the likes of 24 kill ace Gerald R. Johnson once trained, hosts this incredible event as one of its main fund raisers. These days, lucky visitors to Chino can see upwards of forty warbirds thunder overhead.

World War II is slipping from modern memory as the few remaining veterans of it pass. It won’t be long before we won’t have anyone alive who experienced the war at all. But thanks to Planes of Fame, the visceral sensation, the raw power and speed of the planes our grandparents flew in defense of our nation will endure and live in the memories of succeeding generations. Ed Maloney was a visionary, and thanks to his aircraft rescue efforts long before anyone saw value in those aluminum bodies, the sounds and sights of these amazing machines will continue to fill the skies over Southern California for years to come.

World War II is slipping from modern memory as the few remaining veterans of it pass. It won’t be long before we won’t have anyone alive who experienced the war at all. But thanks to Planes of Fame, the visceral sensation, the raw power and speed of the planes our grandparents flew in defense of our nation will endure and live in the memories of succeeding generations. Ed Maloney was a visionary, and thanks to his aircraft rescue efforts long before anyone saw value in those aluminum bodies, the sounds and sights of these amazing machines will continue to fill the skies over Southern California for years to come.

December 16, 1944, the German Army launched the largest offensive operation ever conducted against United States ground forces. Known as the Battle of the Bulge, the fighting raged for over a month and consumed most of the Third Reich’s remaining reserves of fuel and oil. Somewhere between 65,000-125,000 Germans troops were killed, wounded, captured or missing during those furious six weeks of fighting. The U.S. Army suffered more than 89,000 casualties and the loss of over eight hundred armored vehicles and tanks.

December 16, 1944, the German Army launched the largest offensive operation ever conducted against United States ground forces. Known as the Battle of the Bulge, the fighting raged for over a month and consumed most of the Third Reich’s remaining reserves of fuel and oil. Somewhere between 65,000-125,000 Germans troops were killed, wounded, captured or missing during those furious six weeks of fighting. The U.S. Army suffered more than 89,000 casualties and the loss of over eight hundred armored vehicles and tanks.