Men of the 54th Fighter Squadron greet a group of Army nurses on Attu Island during the winter of 1943-44.

Men of the 54th Fighter Squadron greet a group of Army nurses on Attu Island during the winter of 1943-44.

Today is one of those days in American history where a lot of interesting things happened. It is the start of Paul Revere’s ride, the commencement of the bombardment of New Orleans in 1862. The SF Earthquake of 1906 happened today, as did the Doolittle Raid, the Yamamoto Assassination, the 1986 naval skirmish between the U.S. and the Libyans. Tomorrow is the anniversary of the Oklahoma City bombing.

The Doolittle Raid will probably be the most remembered of today’s many anniversaries. On April 18, 1942, sixteen B-25 bombers took off from the USS Hornet and attacked targets in and around Tokyo. The planes flew on to China (one crew made it to Soviet territory), but were all lost in crash landings or the crews bailed out. To the United States populace, starved for any glimmer of good news, the daring raid was a huge lift to national morale. To the Japanese, it was a tremendous shock to discover they were vulnerable to air attack. Their response was to push forward with the Midway plan–and exact revenge on the Chinese.

Most books and articles written about the Raid don’t talk about that latter reaction. Passing mention is made to the fact of the Japanese retribution in China and how most of the airfields the planes were to use were overrun by Imperial Army troops. The truth is that the Chinese paid dearly for America’s propaganda victory.

In the wake of the attacks, Japanese troops destroyed entire cities–one of more than 50,000 people. They killed, raped and tortured hundreds of thousands of Chinese civilians before unleashing bacteriological agents created by Unit 731 upon the surviving population.As a result, cholera and other diseases claimed countless others in the wake of the retribution attacks.

So, today, I want to honor those victims and use my little spot on the web to remind all of us that, while China may be an American economic rival now, our histories are interconnected. The loss of the FilAmerican Army on Bataan was keenly felt in America that April. The Doolittle Raid gave us hope that we could strike back and fight what seemed to many an unstoppable Imperial power. And yet, far more died in China as a result than were captured in the Philippines. Those who so courageously helped our aviators once they were on the ground paid a terrible price. One Chinese civilian was tied up, doused with kerosene and his wife was forced to light him on fire.

For freedom and peace to flourish, those who seek to institutionalize cruelty, who seek to justify barbarism with ideology, must be stopped. World War II taught us that only nations who stand together, put aside their differences and their own faults, can stem that terrible tide. It is a lesson that I wish all our world leaders would remember and take to heart.

For further reading, please check out:

And Scott’s brand new book can be found here:

Though the exploits of the USAAF’s medium bomb groups in the Pacific are well-documented, much less has been written about the U.S. Marine aviators who flew the Mitchell in combat out there alongside the 5th and 13th Air Force B-25 units. The Marines deployed seven PBJ Mitchell squadrons to the Pacific during the war, where they arrived first in the Solomon Islands in early 1944. The Flying Nightmares, VMB-413 earned distinction as the first PBJ outfit to enineter combat. Operating against Rabaul and Kavieng against heavy anti-aircraft opposition, the squadron lost twenty-seven men in its first sixty days in combat. Despite the losses, they had pioneered a new attack technique: While the 5th and 13th Air Force B-25’s pounded New Britain and New Ireland during daylight, the Marines of the ‘413 went in at night.

In May 1943, the Nightmares were pulled out of combat and sent back to refit and reform. VMB-423 replaced 413 that month, and they began combat flights almost immediately. One of the PBJ’s that 423 took into battle had been paid for by a war bond subscription campaign started by some school kids in Oklahoma. By the time it was finished, some 35,000 kids had taken part in the effort. The children had all signed their names on a sixty-five foot long scroll that the unit brought with them to the Solomons. On one of the squadron’s first missions, they dropped the scroll on the Japanese during a bombing raid over Rabaul.

The Oklahoma scroll. Hard to imagine American public schools helping to raise money for combat aircraft today.

More PBJ squadrons arrived in theater during the course of 1944, including VMB-611 which flew its first night raid over Kavieng in November 1944. The following year, most of the PBJ units moved into the Central Pacific and flew from the Marianas, Iwo Jima and Okinawa. VMB-611 went to MAGSZAM–the Marine air formation that supported the Army in the Southern Philippines. VMB-611 under LTC George A. Sarles began flying from Zamboanga, Mindanao in March of 1945. In the two months that followed, they became experts at close air support, blasting targets in front of the 41st Infantry Division and other Army & Filipino guerrilla units fighting to liberate the island from the Japanese.

It was an assignment that received little recognition or publicity. The men of 611 flew constantly, wearing themselves and their aircraft out as their attacks helped minimize Allied ground casualties. They flew 173 sorties in two months. At the end of May, Sarles’ and his crew went down during a bombing run over Japanese defensive positions on Mindanao. Though some of his crew escaped the wreckage and made it back to friendly lines, Sarles was killed. During that spring, VMB-611 suffered nine missing or killed in action, nine wounded and lost four aircraft to the intense Japanese ground fire they encountered on nearly every mission.

VMB-611 was not relieved or rotated out of the line to give the crews a break, as had been standard practice in the South Pacific. Instead, they flew continuously in combat until August 1945 when the war ended.

One PBJ pilot noted that in 50 combat missions, he never saw a Japanese plane in the air. That lack of aerial opposition did not mean their task was an easy one. In seventeen months of fighting in the Pacific, the seven PBJ squadrons lost 45 aircraft and 173 men as they carried out some of the most difficult and unheralded aerial attacks of the war against Japan. The constant strain of night attacks and the seemingly never-ending days of flak-filled skies took a psychological toll on all the crews. At night, friends would sortie on heckling missions, only to never return. Their fates remained unknown and are largely lost to history.

Dedicated to reader David Fish, whose father was one of those PBJ crewmembers who went MIA on a mission with VMB-611 in May 1945.

Forty-two of the fifty members of the Philadelphia South Pacific Club. All hailed from the city of Brotherly Love, and they were by far the largest contingent of men from one spot back home in the Marine Air Groups serving in the 1944 campaign against Rabaul.

The 42nd Bomb Group served as the only B-25 Mitchell outfit in the Thirteenth Air Force during World War II. Going into combat in the Solomon Islands in the summer of 1943, the Crusaders took part in the drive to Bougainville and the isolation of Rabaul. After that campaign, the Thirteenth Air Force moved to New Guinea and became part of FEAF. The 42nd finished the war operating in the Southern Philippines and supporting not only the ground effort there, but also the invasion of Borneo in the Dutch East Indies.

Check out A. Gray’s page: http://waynes-journal.com/about/ for a look into the the day-to-day life of a 42nd Bomb Group tail gunner. It is a terrific site that gives you remarkable insight into the experiences of our American aviators in the SWPA during the war.

In honor of A. Gray and his remarkable website, I’ve posted some photos of the group that I’ve collected over the years:

A B-25 crew from the 42nd practices skip bombing at New Caledonia in the summer of 1943.

Colonel Harry Wilson in the cockpit of his 42nd Bomb Group B-25 at Guadalcanal, 1943.

A dramatic shot of the 42nd during a bombing raid on Bougainville in the fall of 1943.

The Crusaders operating from Munda FIeld, New Georgia during the climactic battles for the Northern Solomons in the fall of 1943.

The Crusader’s flight line at Cape Sansapor, New Guinea.

A 42nd Bomb Group Mitchell roars off target during a low-altitude strike against Sandakan, Borneo in the summer of ’45.

A 42nd Bomg Group B-25 crew gets into their life raft after ditching off Zamboanga, Mindanao in 1945.

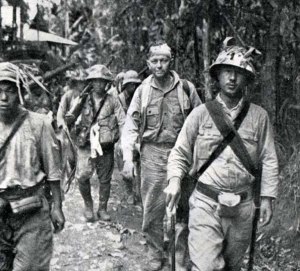

Chinese troops in action against the Japanese Army. The fighting had raged in China for almost five years when Prisoner 529 joined his cavalry brigade there.

On July 7, 1944, an emaciated, fever-wracked twenty-three year old Japanese aviator crept into an Allied camp near Maffin, New Guinea in search of food. He’d been part of about three thousand survivors of the 6th Flying Division, based at Hollandia who had tried to escape the Allied cordon through a torturous overland retreat to Sarmi. For most who set out on this desperate bid for survival, the trek became a death march. Disease, starvation and hostile New Guineans thinned the ranks, and the weak were left behind.

Though his name has been lost to history–we’ll call him Prisoner #529, the five foot four native of Okayama-Ken was one of the lucky few who fell into American hands and survived that crucible in the jungle.

Grateful for food and decent treatment, he spoke freely to the Japanese-Americans who interrogated him after his capture. 529 had been fortunate to have finished twelve years of education, the last three at a commercial school that proved to be a stepping-stone to his first career. He became a wholesale toy salesman until he was conscripted into the Japanese Army at age 20. AS he was leaving to report for duty, his mother wished him farewell with one final order: at all costs, do not allow yourself to be captured.

He was called up at Osaka, where with several hundred other conscripts, he was put on a ship and sent to Korea. From there, they were put on trains to northern China and assigned to the Sakuma Cavalry school for basic training. The cavalry was considered one of the elite arms of the Japanese Army, and Prisoner #529’s intelligence and education probably earned him that coveted slot.

It was hard transition going from the toy business to the cavalry, to say the least. The training was brutal and very intense. He was beaten almost every day, and once his jaw was so badly injured he could barely move it for a week. Another time, three of his squad mates were caught violating rules and the entire squad was assembled and forced to beat each other. Prisoner #529 was slapped by officers, hammered across the back with a wooden cane, whipped with belts and beaten with shoes. Most of the time, 529 felt the punishments were wanton, cruel and unjust. He and his fellow recruits were beaten whether they had did anything wrong or not. Sometimes, infractions were fabricated to justify otherwise inexcusable beatings.

After he told his interrogators about the physical abuse, he added that at times it did work. After all, it “knocked the sloppiness” of the men.

Later that spring, he was assigned to the 1st Cavalry Brigade’s Koike Regiment. One day, #529 and twenty-four other fresh-faced replacements reported for bayonet training near Kitoku, China. When they assembled, five Chinese prisoners were led out to the training ground. Hands bound and blindfolded, their Japanese guards gave them each a drink of water and a cigarette.

Then Colonel Koike ordered the new recruits to bayonet the prisoners.

Bayonet training with live Chinese POW’s was not uncommon during the war. Some twelve million Chinese were killed between 1937-45.

529 had never killed before. He watched as his fellow replacements took turns bayoneting the Chinese prisoners and was deeply moved by the stoic calm of their victims. They didn’t scream, and remained steady and courageous until the end. And the end was not always very fast. Those who survived the initial bayonetings were stabbed repeatedly as each replacement took his turn. The Toy Salesman took his turn with the bayonet, too. Later, he told his interrogators that no Japanese Soldier could have match the quiet resolve of the five Chinese prisoners killed that day.

That moment in Kitoku was a turning point for 529. His quiet life back home spent trying to bring a little happiness into the lives of children was forever behind him. In the months ahead, he watched as his unit and others beheaded and bayoneted Chinese prisoners and those suspected of anti-Japanese activities. Such episodes were common.

In January 1943, he transferred out of the cavalry brigade and joined the 41st Division at Soken (still in Northern China). He remained there for only a short time before being ordered to New Guinea. On May 1, 1943, he reached Wewak in the Zuisho Maru (which would be torpedoed and sunk a few months later off the Borneo coast by the American submarine Ray).

From the cavalry to the infantry and now in New Guinea, Prisoner 529 became an aerial gunner. He went through a crash, ten week course at Hollandia before joined the 208th Sentai, a Kawasaki Ki-48 “Lilly” medium bomber regiment.

It was at Hollandia he came to realize the hopelessness of Japan’s situation in New Guinea. He’d gone to China, an eager and willing recruit. who viewed the war as a titanic clash between races. He was anxious to prove himself and serve his country in this epochal moment in history. Even the atrocities to which he bore witness and participated in during his time in China did not diminish that sentiment. When he received orders to the Southwest Pacific Area, he looked forward to carrying his nation’s flag to new, exciting and distant places.

The nose gun mount in a Ki-48. Prisoner 529 told his interrogator that the mount was so restrictive that it only had a 45 degree field of fire.

In New Guinea, the constant air attacks, the lack of supplies and rare mail deliveries drove that eagerness out of him. The war devolved into a bitter struggle for survival on an alien island while increasingly surrounded by Allied forces. Disease became an ever present enemy. The men cleared brush from around their quarters in hopes of deterring insects and slept under mosquito nets at night. During Allied air raids, they would take to their bomb shelters wearing nets over their heads and gloves. To stave off malaria, the men took daily doses of both quinine and atebrin. Despite their best efforts, the men were plagued by tropical infections and fungus. By early 1944, almost everyone in 529’s squadron suffered from ringworm and other skin diseases.

529’s squadron included fifteen Ki-48 Lilly’s, fifteen pilots and radio operators, sixty gunners and about a hundred and twenty ground crewmen. The regiment had forty planes total, half of which were destroyed in a series of Allied raids in the spring of 1944 at both Wewak and Hollandia.

While other Ki-48 units had new models with heavier armament, the 208th’s planes were equipped with only five machine guns–one 7.9mm in the nose, another in the ventral position, a pair of 7.7mm waist guns and a single 13mm for the dorsal gunner. That latter position was a tricky one, and the gunners had gone through extra training for it since it was very easy to accidentally shoot the tail off. Prisoner 529 had been told cautionary tales of dorsal gunners who sawed their vertical fins and rudders off in their eagerness to hit an incoming enemy fighter. The result was usually fatal.

During daylight missions, the 208th flew with five men in each aircraft: a pilot (who also doubled as navigator), a radio operator, waist gunner, nose and dorsal gunners. The radioman also manned the ventral gun. At night, they left the waist gunner on the airfield and flew with four. They had no trained bombardiers ala the USAAF. Usually, either the pilot or the nose gunner would toggle the aircraft’s six 50 kg bombs that composed its normal load out. Exactly who did that was left to the individual crews to decide, but usually the senior or more experienced man got the job.

A 5th Air Force P-39’s gun camera film records the final moments of a KI-48. The radio operator’s ventral gun position can be seen under the fuselage.

To increase the Lilly’s range, the 208th Sentai’s bombers had an additional fuel tank mounted inside the fuselage in front of the radio operator’s seat. Three feet long, three feet high and about twenty inches wide, it was not armored and not self-sealing. This meant a single bullet strike could have ignited the tank, bathing the radio operator in flaming gasoline.

On missions, the 208th carried out most of its attacks at between ten and twelve thousand feet. On a few knuckle-biting ones, however, the crews used their Ki-48’s like dive bombers, nosing over and making steep angle descents to three thousand feet before pickling their loads.

Mission briefings were far more informal than in the USAAF. Usually, the squadron commander would select the aircraft and crews the night before the attack. In the morning, just before take-off, the aviators would be given the target, the approach to it and any special instructions specific to the mission. When they returned, each plane captain would give an oral report to the squadron commander.

Intelligence on the Allies was minimal and very restricted. Prisoner #529 rarely even saw a map while he was in New Guinea, as those were reserved for the officers. Most of the time, they did not even know what their targets looked like.

To #529, defeat looked inevitable. Yet, he also believed that no matter what followed, the Japanese people would fight to the last man, and woman.

During the spring of 1944, Allied air attacks repeatedly struck the 208th airfields at both Hollandia and Wewak. At Hollandia, the raids seemed particularly accurate, as if the Allies knew the exact location of every building, revetment and aircraft. (Thanks to the 5th Air Force’s reconnaissance efforts, they did). By April, every facility on the strip at Hollandia had been bombed to splinters, though the 208th did not lose many men in these attacks thanks to the many shelters and slit trenches constructed for them.

The B-25 Mitchell was particularly feared. Racing in at low altitude with their nose guns blazing, dropping parafrags in their wake, these American bombers destroyed fuel dumps, blew up grounded aircraft, wiped out anti-aircraft positions and terrified all those exposed to their strafing. With eight to twelve .50 caliber machine guns in the nose of each B-25, the gunships were devastating weapons.

The 5th Air Force’s B-24’s were also greatly feared. Though they made their attacks from higher altitudes, their accuracy astonished the Japanese. The 208th concluded that the Liberators had to have had bomb sights far superior to what Japan had produced.

In April 1944, the Allies launched a surprise amphibious invasion at Hollandia. The Oregon and Washington National Guard division, the 41st, quickly stormed ashore and secured the airfields there. There were few Japanese combat troops in the area, and Prisoner 529 fled into the jungle with the rest of his unit when the landings began.

Chased by American patrols, without food or good weapons or supplies of any kind, the three thousand survivors from 529’s air division attempted to make it to Sarmi, a small Japanese outpost on the coast, some one hundred fifty miles west of Hollandia. For months, the survivors plodded through the jungle, only to discover the Americans had outflanked them again at Wakde and Maffin Bay. The altogether, there were probably about twenty thousand Japanese on this trek for survival, including the remains of the 224th Infantry Regiment.

In mid-June, a battle raged for almost two weeks around a six thousand foot tall mountain overlooking Maffin Bay. Known as the Battle of Lone Tree Hill, the Japanese lost over a thousand men in direct combat with the Americans—and at least another eleven thousand to starvation. Afterwards, the Japanese retreating from Hollandia had little hope left. With Americans behind them, the ocean to their right flank, the inhospitable mountains on their left, they’d come through the jungle only to find the path ahead firmly in American hands.

The 5th Air Force raids on Wewak and Hollandia between August 1943 and the spring of 1944 broke the back of the Japanese Army Air Force. Most of its units in the SWPA were completely wiped out, with few of the air or ground crews escaping to fight another day.

The survivors scattered, breaking into small groups to forage for food and try to find some friendly garrison to join. Most died of disease or starvation. Some resorted to cannibalism, preying on other Japanese or on local New Guinea natives.

Prisoner #529 remained in the Maffin Bay area after Lone Tree Hill ended, hoping to steal food from an American encampment. Instead, he was caught and captured, a source of utter humiliation to him. He felt he’d let his mother down, and that if he were to ever return to Japan, he would be court-martialed for allowing himself to become a prisoner. To his surprise, he found Americans to be jovial and mostly friendly toward him. In training, he had been told the Americans would kill him if he ever surrendered. Instead, he found them “outgoing, liberal and happy.”

After reconciling himself with his situation, his sense of humiliation at his capture gradually drained away. He began to dream of life post-war, and he hoped that he could settle in Australia and become a farmer.

Of the 250,000 Japanese troops, aviators and sailors sent to New Guinea during the war, less than 15,000 survived the war and returned to Japan. In 1949, eight Japanese hold-outs were discovered living in a village a hundred miles from Madang, New Guinea. They surrendered and returned to Japan in February 1950, possibly the last survivors from the New Guinea campaign to do so.

Private First Class John Legg grew up in Tioga, West Virginia, another of Depression Era kid who sought escape and opportunity through service to his country. He joined the Army Air Force, where he was trained to be a teletype operator and clerk.

Private First Class John Legg grew up in Tioga, West Virginia, another of Depression Era kid who sought escape and opportunity through service to his country. He joined the Army Air Force, where he was trained to be a teletype operator and clerk.

On December 8, 1941, Legg was stationed at Nielson Field on Luzon, Philippines, and might have been one of the clerks who sent the teletype warning to Clark Field that it was about to be hit by a Japanese air attack. Legg was an aspiring writer who wanted to pen a novel about the Philippines. His experiences there had given him much inspiration, and he’d been keeping notes for what he hoped would be his first book. In his off-duty hours, he wrote poetry as well.

He was not a rifleman; he was not a special operations sniper. Legg was one of those anonymous young Americans who carried out one of the mundane daily duties that keeps a military organization functioning. The jobs have zero glamour, and historians rarely even make mention of their jobs, let alone those who filled them. Legg was captured when the Philippines fell in the spring of 1942. He survived the Death March and made it to Cabantuan prison camp, but the ordeal had wrecked his health. He steadily declined, suffering from dysentery and malaria until he died on August 16, 1942.

His mother was notified via telegram the following year of his death. A short letter followed the telegram a week later. It ended with this sentence:

“May the thought that he gave his life for his country as unselfishly and heroically as if he had died on the field of battle, be a source of sustaining comfort to you.”

Small comfort to a West Virginia mother who would not even learn of the exact date of her son’s death until 1946.

John Legg had a writer’s eye and heart. In On Writing, Stephen King wrote that most people either are born with the talent and it can be honed, or they just don’t have it. No amount of effort or work can replace that innate gene that makes a truly gifted writer. Legg was one of those who had the innate talent.

The world lost a beautiful mind when he died in captivity. Had he lived and realized his potential, one wonders how his words could have affected and changed those who read them. His death was but a tiny piece of a mosiac that stretched the globe. So much lost potential. So many discoveries, inventions, changes and art lost to all of us with the deaths of so many souls. One wonders how much further we could have advanced and evolved as a species had we not lost so many millions like young John Legg.

Only a few examples of his talent survive. Here is one of his poems that he wrote sometime in 1941 while feeling far from home out on the edge of America’s Pacific ramparts.

Dreamer’s Haven

Beyond the fields of clover bloom

Beyond wheat fields so green

Far past the dust of traveled roads

Where travelers all convene.

Where we hear not the rattling wagon

The hum and grind of the mill

There is a place, known just to me

Where everything is still

A path lies winding through the woods

And leads to a sheltered grove

Of maple, beech, dogwood and pine

That form a shaded cove.

Within, a space is almost bare

Of briars and vines that creep

And here a carpet of flowers and moss,

Lies green, and soft, and deep.

A sparkling spring from an unknown depth

Flows upward; in it one finds

A thirst consoling, icy draft

Sweeter than goblets of wine.

The silence is unbroken here

Hour after hour the same

Unless a bird calls to its mate

Or a tree frog croaks for rain.

In this shaded cover, one soon may be

In the peace of contentment, the best

And knowing there is naught to harm

One may think, or in sleep, on may rest.

In the stillness one’s thoughts often wonder

To things gone behind, far away.

One remembers some happenings of life,

With gladness, and others….dismay.

Your dreams are made real by surroundings,

You picture a castle so fair

And awake to find sad disappointments,

In that your dreams vanished in air.

And then one may just sit and gaze

Into the sky, so far away, so blue.

And think how happy you would be

If only your dreams could come true.

If you are sometimes tired of life,

When friends forget, and there seems

To be no joy, break away and come

To the woodland cove, and dream.

–PFC John M. Legg

Stevenot (at right) in 1917 with the son of the first Philippine President.

On Sunday December 7, 1941, a dapper, fiftysomething American businessman climbed into Philippine Air Lines’ only Beech Staggerwing for an unusual charter flight from Manila’s Nieslon Field to a remote jungle airstrip in southeastern Luzon. Joseph Stevenot was a legend in the Philippines by this time. Born in 1888, he played a pioneering role in the development of aviation in the Philippines just after the Great War. He’d served in the National Guard and ran the Army’s aviation section on Luzon. Later, he became Curtiss’ tech rep in the Far East and established a flying school under the company’s auspices. He and one other American trained the first Filipino military aviators, flew the first aircraft into Cebu (it was a mail run) and pioneered many other aspects of aviation in the Philippines.

The box the PAL Staggerwing came in. It had been Andres Sorianos’ private aircraft through the 1930’s, and Paul Gunn had come out to Manila to be his personal pilot in 1939. Later, Sorianos and his business partners established Philippine Air Lines, and Paul Gunn was hired to be its operations manager.

In the 1920’s, he helped consolidate the many different telephone companies in the Philippines into one corporation, and he became the vice president of operations for Philippine Long Distance Telephone and Telegraph (PLTD). He made many friends in high places, and his family’s connections back in California also played a role in his many successful business ventures, including a mine operation company he started in the 1930’s. He hailed from one of the wealthiest families of the Sunshine State, where one of his brothers was perhaps the most successful hotel owner of his era and another was a senior executive with Bank of America.

He was known as a bon vivant, charming and charismatic. He moved easily through Manila’s high society, where his comings and goings were reported by the local press. In 1936, he was one of seven men who officially established the Boy Scouts of the Philippines, and he took an interest in scouting through the next five years.

The PAL hangar at Nielson Field, the Staggerwing at right.

In July 1941, Stevenot was back in Washington D.C., and he met with Secretary of War Henry Stimson to urge him to build a closer relationship with the commanders in the Philippines. He advocated for a higher defense budget for the islands as well on other occasions.

Through all his entrepreneurial efforts, he remained an Army reservist. He’d been a major for almost twenty years as he built out his life in Manila.

In the fall of 1941, Stevenot and PLTD played a key role in the development of the USAAF’s air defenses in the Philippines. Radar sets had just started arriving in the the islands, but it would be months before radar coverage would be anywhere near adequate. To spot incoming Japanese aircraft, a broad network of aerial observers was established, similar to what the British had during the Battle of Britain in 1940. These posts were scattered all over Luzon and manned mainly by Filipinos. Stevenot oversaw the construction of the phone lines that tied all this vital network into the air plotting center that had just been built at Nielson Field that fall.

On December 7th, Stevenot flew in the PAL Beech to a tiny jungle airstrip right on the water at Paracale, a tiny mining community a hundred and twenty miles southeast of Manila. Paul “P.I.” Gunn piloted the Staggerwing that day right into a raging storm that had turned the Paracale area into a sea of mud. When they touched down there, the Beech was damaged beyond local repair. Parts were later brought out to it, the plane repaired and flown back to Manila.

The next morning, Monday December 8, 1941, Paul Gunn learned of the attack on Pearl Harbor and made an epic trek back to Manila by boat, train and bus in order to be with his family. But Stevenot stayed behind at Paracale for almost a week.

What was the sixtysomething businessman doing out there on the coast that was so important Paul Gunn had to fly him through a near-monsoon to get him there?

As I’ve been writing the initial chapters of Indestructible, my biography of Paul “Pappy” Gunn, Stevenot’s trip has both fascinated and frustrated me. His letters archived at the University of the Pacific in Stockton, CA., make no reference to that trip. He just wrote his family that he was doing interesting stuff that he couldn’t talk about.

There were a series of gold mines at Paracale that I thought may have been the reason for the trip out there. The PAL Beech made weekly runs to the strip there to carry out about 125 lbs of gold per flight, but making that trip on a Sunday in terrible weather seemed unlikely . Perhaps Stevenot had a crisis he needed to handle at one of the mines his company operated? Nope. I tracked down the ownership and operating companies of those mines and discovered that none of them were run or owned by Stevenot’s corporation. His mining operations were all further south.

Then I made a startling discovery. The USAAF had sent a detachment from an early warning company out to Paracale, by ship to establish two radar sites in the area. One was supposed to be a permanent facility using an SCR-271 radar that had arrived in the Philippines that October. The other was a mobile set similar to the one seen in the movie Tora Tora Tora.

Then I made a startling discovery. The USAAF had sent a detachment from an early warning company out to Paracale, by ship to establish two radar sites in the area. One was supposed to be a permanent facility using an SCR-271 radar that had arrived in the Philippines that October. The other was a mobile set similar to the one seen in the movie Tora Tora Tora.

The men in that detachment were unhappy campers. When they reached Paracale, there were no facilities of any kind for them. They’d basically been thrown out on the edge of nowhere without any logistical support, or even a place to stay. The NCO’s were able to find a partially empty warehouse, and the men ended up calling that home for the next several weeks. Meanwhile, the det commander, a brilliant electronics specialist named Lt. Jack Rogers, bunked down in one of the mining company’s club houses. That was relative luxury compared to what the men were dealing with, and that caused a lot of internal rancor that lingered for decades.

Stevenot was not only a telephone and telegraph expert, but he’d overseen the construction of teletype networks and radio telephone facilities all over the Philippines. He’d set up the first trans-Pacific phone line to the the United States, and in the early 30’s he’d made headlines when he and eleven of his family members carried on a party line phone conversation from all over California and Manila.

In short, Stevenot was an expert in modern communication systems.

Rogers’ air warning det had taken the mobile radar set, an SCR-270, and dragged it up the side of steep mountain overlooking the water outside of Paracale. They’d set it up and got it running on December 6th, but only Rogers knew anything about how to use it. The men were so untrained that later they missed the signature of a B-17 coming over them en route to Legaspi. Only when it buzzed right over their heads did they learn of its presence in their airspace. They’d also had no time to calibrate the fussy electronics, which made it virtually useless even with operators who knew how to make it work.

There was no phone lines tying the mobile site to the plotting center at Nielson. All communication from Paracale to their chain of command back around Manila was conducted by radio, which problematical thanks to the rugged mountains in the area.

The SCR-271 set was supposed to be the basis of a permanent air warning site, but it had not been uncrated by December 8th when the Japanese attacks began. But, all the sites were supposed to be tied into Nielson via the same sort of phone adn teletype network the observer stations and other bases used.

Paracale did have phone service, so Stevenot was probably out there on December 7th to check out the new det and figure out ways to get better commo to their mountainous post.

Of course, it was too little, too late. The Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor that Monday Philippines time, and by lunch, Clark Field lay under a towering cloud of smoke and flames. Stevenot stayed at Paracale and even reported (by phone) sighting a Japanese invasion force off shore on December 13th.

Lt. Rogers’ det was ordered back to Manila after the Japanese landed in Southern Luzon. Much of the equipment was lost–abandoned or blown up as the Japanese approached, and several members of the det were either killed in action or were separated from their brothers and ended up fighting on as guerrillas. The rest made it back to Manila in time to retreat into Bataan. Those who survived the next four months endured the Death March, captivity and the Hell Ships.

Stevenot returned to MacArthur’s headquarters and retreated to Corregidor with the general’s staff at the end of December. He arrived on the Rock with a big box labeled “Signal Corps Tubes.” Actually, the box was full of good hooch, which General Charles Willoughby never forgot. In his post-war memoirs, Willoughby wrote about Stevenot busting out shots of his good stuff whenever morale was down or the FilAmerican Army had suffered another bad day.

Meanwhile, Stevenot kept a direct line open from the Manila switchboard to the yacht basin on the Rock. He would go down there and talk to his fearless employee, a female operator, who used the line as a way to eavesdrop on Japanese military conversations. After taking Manila, the senior Japanese officers used the phone system like anyone else, and those conversations yielded a gold mine of intelligence until February 1942. By then, word of how the Japanese were treating the local Filipino population had reached MacArthur’s staff, and Stevenot decided he couldn’t keep endangering his employee. He’d learned that a niece of his in Manila had been seized and tortured by the Japanese in an effort to get her to reveal Stevenot’s location, and that might have contributed to his caution in this case.

Stevenot remained on the Rock until almost the very end. But after MacArthur made it to Australia, he personally ordered Stevenot out on one of the last submarines to reach Manila Bay. He was evacuated just before the Japanese landed on Corregidor in May.

Stevenot remained on the Rock until almost the very end. But after MacArthur made it to Australia, he personally ordered Stevenot out on one of the last submarines to reach Manila Bay. He was evacuated just before the Japanese landed on Corregidor in May.

He served through 1942 and the spring of 1943 throughout the SWPA, never revealing to his family what role he was playing on behalf of MacArthur’s GHQ. He was promoted to LTC then full bird colonel. In June 1943, he died in a plane crash in the New Hebrides Islands. MacArthur wrote a personal letter of condolence to his widow.

Despite searching through the GHQ records at the MacArthur Memorial, I’ve been unable to determine exactly what Colonel Joseph Stevenot was doing for the U.S. Army in 1941-43. Lists of officers and their official positions do not include him. Yet, the Japanese knew who he was and were anxious to find him. Whether it was for his role as a civilian senior executive, or for his military role remains a mystery, as does so much of his last two years of life. Whatever the case, MacArthur deemed him an essential officer who could not be allowed to fall into Japanese hands. And the Japanese considered him so important they tortured at least one woman to try and locate him.

So, I thought I’d do this: If anyone has any further information on Joseph Stevenot, I would love to hear from you. While he is just a passing character in the book I’m writing, his fascinating life and accomplishments have become of great interest to me. In the meantime, he’ll remain the mysterious major of Indestructible‘s early chapters.

John R. Bruning

An Aichi D3A Val under the guns of a 348th Fighter Group P-47 pilot over Arawe, New Britain, December 27, 1943.

Robert Sutcliffe, a Thunderbolt pilot assigned to the 348th Fighter Group, makes a pass on a formation of Japanese bombers over Cape Gloucester, New Britain on Boxing Day 1943.

Lawrence O’Neil, another 348th Fighter Group P-47 pilot, making a low side pass on the same bomber formation Sutcliffe attacked on December 26, 1943.

George Orr, 348th FG, making a stern attack on a Japanese bomber over Cape Gloucester, December 26, 1943.