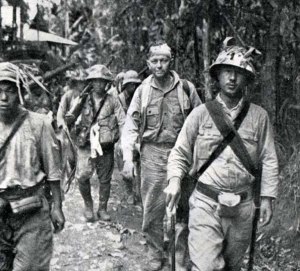

Chinese troops in action against the Japanese Army. The fighting had raged in China for almost five years when Prisoner 529 joined his cavalry brigade there.

On July 7, 1944, an emaciated, fever-wracked twenty-three year old Japanese aviator crept into an Allied camp near Maffin, New Guinea in search of food. He’d been part of about three thousand survivors of the 6th Flying Division, based at Hollandia who had tried to escape the Allied cordon through a torturous overland retreat to Sarmi. For most who set out on this desperate bid for survival, the trek became a death march. Disease, starvation and hostile New Guineans thinned the ranks, and the weak were left behind.

Though his name has been lost to history–we’ll call him Prisoner #529, the five foot four native of Okayama-Ken was one of the lucky few who fell into American hands and survived that crucible in the jungle.

Grateful for food and decent treatment, he spoke freely to the Japanese-Americans who interrogated him after his capture. 529 had been fortunate to have finished twelve years of education, the last three at a commercial school that proved to be a stepping-stone to his first career. He became a wholesale toy salesman until he was conscripted into the Japanese Army at age 20. AS he was leaving to report for duty, his mother wished him farewell with one final order: at all costs, do not allow yourself to be captured.

He was called up at Osaka, where with several hundred other conscripts, he was put on a ship and sent to Korea. From there, they were put on trains to northern China and assigned to the Sakuma Cavalry school for basic training. The cavalry was considered one of the elite arms of the Japanese Army, and Prisoner #529’s intelligence and education probably earned him that coveted slot.

It was hard transition going from the toy business to the cavalry, to say the least. The training was brutal and very intense. He was beaten almost every day, and once his jaw was so badly injured he could barely move it for a week. Another time, three of his squad mates were caught violating rules and the entire squad was assembled and forced to beat each other. Prisoner #529 was slapped by officers, hammered across the back with a wooden cane, whipped with belts and beaten with shoes. Most of the time, 529 felt the punishments were wanton, cruel and unjust. He and his fellow recruits were beaten whether they had did anything wrong or not. Sometimes, infractions were fabricated to justify otherwise inexcusable beatings.

After he told his interrogators about the physical abuse, he added that at times it did work. After all, it “knocked the sloppiness” of the men.

Later that spring, he was assigned to the 1st Cavalry Brigade’s Koike Regiment. One day, #529 and twenty-four other fresh-faced replacements reported for bayonet training near Kitoku, China. When they assembled, five Chinese prisoners were led out to the training ground. Hands bound and blindfolded, their Japanese guards gave them each a drink of water and a cigarette.

Then Colonel Koike ordered the new recruits to bayonet the prisoners.

Bayonet training with live Chinese POW’s was not uncommon during the war. Some twelve million Chinese were killed between 1937-45.

529 had never killed before. He watched as his fellow replacements took turns bayoneting the Chinese prisoners and was deeply moved by the stoic calm of their victims. They didn’t scream, and remained steady and courageous until the end. And the end was not always very fast. Those who survived the initial bayonetings were stabbed repeatedly as each replacement took his turn. The Toy Salesman took his turn with the bayonet, too. Later, he told his interrogators that no Japanese Soldier could have match the quiet resolve of the five Chinese prisoners killed that day.

That moment in Kitoku was a turning point for 529. His quiet life back home spent trying to bring a little happiness into the lives of children was forever behind him. In the months ahead, he watched as his unit and others beheaded and bayoneted Chinese prisoners and those suspected of anti-Japanese activities. Such episodes were common.

In January 1943, he transferred out of the cavalry brigade and joined the 41st Division at Soken (still in Northern China). He remained there for only a short time before being ordered to New Guinea. On May 1, 1943, he reached Wewak in the Zuisho Maru (which would be torpedoed and sunk a few months later off the Borneo coast by the American submarine Ray).

From the cavalry to the infantry and now in New Guinea, Prisoner 529 became an aerial gunner. He went through a crash, ten week course at Hollandia before joined the 208th Sentai, a Kawasaki Ki-48 “Lilly” medium bomber regiment.

It was at Hollandia he came to realize the hopelessness of Japan’s situation in New Guinea. He’d gone to China, an eager and willing recruit. who viewed the war as a titanic clash between races. He was anxious to prove himself and serve his country in this epochal moment in history. Even the atrocities to which he bore witness and participated in during his time in China did not diminish that sentiment. When he received orders to the Southwest Pacific Area, he looked forward to carrying his nation’s flag to new, exciting and distant places.

The nose gun mount in a Ki-48. Prisoner 529 told his interrogator that the mount was so restrictive that it only had a 45 degree field of fire.

In New Guinea, the constant air attacks, the lack of supplies and rare mail deliveries drove that eagerness out of him. The war devolved into a bitter struggle for survival on an alien island while increasingly surrounded by Allied forces. Disease became an ever present enemy. The men cleared brush from around their quarters in hopes of deterring insects and slept under mosquito nets at night. During Allied air raids, they would take to their bomb shelters wearing nets over their heads and gloves. To stave off malaria, the men took daily doses of both quinine and atebrin. Despite their best efforts, the men were plagued by tropical infections and fungus. By early 1944, almost everyone in 529’s squadron suffered from ringworm and other skin diseases.

529’s squadron included fifteen Ki-48 Lilly’s, fifteen pilots and radio operators, sixty gunners and about a hundred and twenty ground crewmen. The regiment had forty planes total, half of which were destroyed in a series of Allied raids in the spring of 1944 at both Wewak and Hollandia.

While other Ki-48 units had new models with heavier armament, the 208th’s planes were equipped with only five machine guns–one 7.9mm in the nose, another in the ventral position, a pair of 7.7mm waist guns and a single 13mm for the dorsal gunner. That latter position was a tricky one, and the gunners had gone through extra training for it since it was very easy to accidentally shoot the tail off. Prisoner 529 had been told cautionary tales of dorsal gunners who sawed their vertical fins and rudders off in their eagerness to hit an incoming enemy fighter. The result was usually fatal.

During daylight missions, the 208th flew with five men in each aircraft: a pilot (who also doubled as navigator), a radio operator, waist gunner, nose and dorsal gunners. The radioman also manned the ventral gun. At night, they left the waist gunner on the airfield and flew with four. They had no trained bombardiers ala the USAAF. Usually, either the pilot or the nose gunner would toggle the aircraft’s six 50 kg bombs that composed its normal load out. Exactly who did that was left to the individual crews to decide, but usually the senior or more experienced man got the job.

A 5th Air Force P-39’s gun camera film records the final moments of a KI-48. The radio operator’s ventral gun position can be seen under the fuselage.

To increase the Lilly’s range, the 208th Sentai’s bombers had an additional fuel tank mounted inside the fuselage in front of the radio operator’s seat. Three feet long, three feet high and about twenty inches wide, it was not armored and not self-sealing. This meant a single bullet strike could have ignited the tank, bathing the radio operator in flaming gasoline.

On missions, the 208th carried out most of its attacks at between ten and twelve thousand feet. On a few knuckle-biting ones, however, the crews used their Ki-48’s like dive bombers, nosing over and making steep angle descents to three thousand feet before pickling their loads.

Mission briefings were far more informal than in the USAAF. Usually, the squadron commander would select the aircraft and crews the night before the attack. In the morning, just before take-off, the aviators would be given the target, the approach to it and any special instructions specific to the mission. When they returned, each plane captain would give an oral report to the squadron commander.

Intelligence on the Allies was minimal and very restricted. Prisoner #529 rarely even saw a map while he was in New Guinea, as those were reserved for the officers. Most of the time, they did not even know what their targets looked like.

To #529, defeat looked inevitable. Yet, he also believed that no matter what followed, the Japanese people would fight to the last man, and woman.

During the spring of 1944, Allied air attacks repeatedly struck the 208th airfields at both Hollandia and Wewak. At Hollandia, the raids seemed particularly accurate, as if the Allies knew the exact location of every building, revetment and aircraft. (Thanks to the 5th Air Force’s reconnaissance efforts, they did). By April, every facility on the strip at Hollandia had been bombed to splinters, though the 208th did not lose many men in these attacks thanks to the many shelters and slit trenches constructed for them.

The B-25 Mitchell was particularly feared. Racing in at low altitude with their nose guns blazing, dropping parafrags in their wake, these American bombers destroyed fuel dumps, blew up grounded aircraft, wiped out anti-aircraft positions and terrified all those exposed to their strafing. With eight to twelve .50 caliber machine guns in the nose of each B-25, the gunships were devastating weapons.

The 5th Air Force’s B-24’s were also greatly feared. Though they made their attacks from higher altitudes, their accuracy astonished the Japanese. The 208th concluded that the Liberators had to have had bomb sights far superior to what Japan had produced.

In April 1944, the Allies launched a surprise amphibious invasion at Hollandia. The Oregon and Washington National Guard division, the 41st, quickly stormed ashore and secured the airfields there. There were few Japanese combat troops in the area, and Prisoner 529 fled into the jungle with the rest of his unit when the landings began.

Chased by American patrols, without food or good weapons or supplies of any kind, the three thousand survivors from 529’s air division attempted to make it to Sarmi, a small Japanese outpost on the coast, some one hundred fifty miles west of Hollandia. For months, the survivors plodded through the jungle, only to discover the Americans had outflanked them again at Wakde and Maffin Bay. The altogether, there were probably about twenty thousand Japanese on this trek for survival, including the remains of the 224th Infantry Regiment.

In mid-June, a battle raged for almost two weeks around a six thousand foot tall mountain overlooking Maffin Bay. Known as the Battle of Lone Tree Hill, the Japanese lost over a thousand men in direct combat with the Americans—and at least another eleven thousand to starvation. Afterwards, the Japanese retreating from Hollandia had little hope left. With Americans behind them, the ocean to their right flank, the inhospitable mountains on their left, they’d come through the jungle only to find the path ahead firmly in American hands.

The 5th Air Force raids on Wewak and Hollandia between August 1943 and the spring of 1944 broke the back of the Japanese Army Air Force. Most of its units in the SWPA were completely wiped out, with few of the air or ground crews escaping to fight another day.

The survivors scattered, breaking into small groups to forage for food and try to find some friendly garrison to join. Most died of disease or starvation. Some resorted to cannibalism, preying on other Japanese or on local New Guinea natives.

Prisoner #529 remained in the Maffin Bay area after Lone Tree Hill ended, hoping to steal food from an American encampment. Instead, he was caught and captured, a source of utter humiliation to him. He felt he’d let his mother down, and that if he were to ever return to Japan, he would be court-martialed for allowing himself to become a prisoner. To his surprise, he found Americans to be jovial and mostly friendly toward him. In training, he had been told the Americans would kill him if he ever surrendered. Instead, he found them “outgoing, liberal and happy.”

After reconciling himself with his situation, his sense of humiliation at his capture gradually drained away. He began to dream of life post-war, and he hoped that he could settle in Australia and become a farmer.

Of the 250,000 Japanese troops, aviators and sailors sent to New Guinea during the war, less than 15,000 survived the war and returned to Japan. In 1949, eight Japanese hold-outs were discovered living in a village a hundred miles from Madang, New Guinea. They surrendered and returned to Japan in February 1950, possibly the last survivors from the New Guinea campaign to do so.

Then I made a startling discovery. The USAAF had sent a detachment from an early warning company out to Paracale, by ship to establish two radar sites in the area. One was supposed to be a permanent facility using an SCR-271 radar that had arrived in the Philippines that October. The other was a mobile set similar to the one seen in the movie Tora Tora Tora.

Then I made a startling discovery. The USAAF had sent a detachment from an early warning company out to Paracale, by ship to establish two radar sites in the area. One was supposed to be a permanent facility using an SCR-271 radar that had arrived in the Philippines that October. The other was a mobile set similar to the one seen in the movie Tora Tora Tora.

Stevenot remained on the Rock until almost the very end. But after MacArthur made it to Australia, he personally ordered Stevenot out on one of the last submarines to reach Manila Bay. He was evacuated just before the Japanese landed on Corregidor in May.

Stevenot remained on the Rock until almost the very end. But after MacArthur made it to Australia, he personally ordered Stevenot out on one of the last submarines to reach Manila Bay. He was evacuated just before the Japanese landed on Corregidor in May. This week, Bloomberg News reported that the new Secretary General of NATO, Jens Stoltenberg, was in Washington D.C. for meetings and asked the White House for some time with the President while he was here. According to reports, the White House staff did not even respond. This broke with a long standing tradition that when the Secretary General of NATO was in D.C., the President always made time to see him. Full article is here: http://www.bloombergview.com/articles/2015-03-24/obama-snubs-nato-chief-as-crisis-rages.

This week, Bloomberg News reported that the new Secretary General of NATO, Jens Stoltenberg, was in Washington D.C. for meetings and asked the White House for some time with the President while he was here. According to reports, the White House staff did not even respond. This broke with a long standing tradition that when the Secretary General of NATO was in D.C., the President always made time to see him. Full article is here: http://www.bloombergview.com/articles/2015-03-24/obama-snubs-nato-chief-as-crisis-rages.

Despite the German invasion and the Luftwaffe’s depredations, the fleet survived virtually intact. When King Haakon reached London, he delivered the 4.8 million ton Norwegian merchant marine to the Allied cause. This was manna from heaven for Great Britain, whose survival soon depended on these ships. By 1942, forty percent of Britain’s oil rode to the Home Islands aboard Norwegian tankers. Without their contribution, England would surely have been doomed, but the Norwegian crews never received credit for this crucial component to the Allied victory.

Despite the German invasion and the Luftwaffe’s depredations, the fleet survived virtually intact. When King Haakon reached London, he delivered the 4.8 million ton Norwegian merchant marine to the Allied cause. This was manna from heaven for Great Britain, whose survival soon depended on these ships. By 1942, forty percent of Britain’s oil rode to the Home Islands aboard Norwegian tankers. Without their contribution, England would surely have been doomed, but the Norwegian crews never received credit for this crucial component to the Allied victory.