The GTO & Dunker Church on the Antietam Battlefield.

As some of you know, I’ve spent much of this summer crossing the country in my little black ’06 Pontiac GTO, stopping at various places & archives to do research for my forthcoming book. I’m over 6,000 miles on this trip so far, and when I’m moving between points important to the next book, I often either get lost or sidetracked. Some of the best moments from this trip have come that way.

Stopped at Burnside’s Bridge on the Antietam battlefield en route to the National Archives.

Earlier this week, I drove through the Shenandoah Valley, spent the night in Bull’s Gap, Tennessee, and reached Chattanooga in time for lunch. It had rained all day, but the weather began to clear so I drove up Lookout Mountain to see what remained of the battlefield.

In the fall of 1863, Confederate troops laid siege to Chattanooga. The Union Army was surrounded and running out of food. The Southerners held the high ground–Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge–so the Union troops were pretty much always under observation or under the guns of Confederate artillery batteries.

In the fall of 1863, Confederate troops laid siege to Chattanooga. The Union Army was surrounded and running out of food. The Southerners held the high ground–Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge–so the Union troops were pretty much always under observation or under the guns of Confederate artillery batteries.

In November 1863, the Union Army broke the siege after the arrival of reinforcements. Union troops inside Chattanooga launched a surprise assault up Lookout Mountain on a foggy morning that obscured much of the peak from view. The fighting literally took place inside that cloud bank until the Union troops pushed forward and up Lookout Mountain. There, they broke out into clear skies and fought on with the fog bank below them in an almost surreal visual that later prompted the engagement to be nicknamed, “The Battle Above the Clouds.”

When I arrived, the clouds were indeed still below the peak after the rainstorm, providing a glimpse of that surreal situation back in 1863.

I walked a bit of the battlefield, astonished at the ruggedness of the terrain. In this day and age, mountain warfare troops would have been employed to take this mountain. The fighting was point-blank–under a hundred yards–with the fog bank obscuring visibility and making it difficult to tell friend from foe. Hand-to-hand combat raged on the slopes near a farm called the Craven House, and hundreds of men were cut down in the vicious fighting. Ultimately, the Union attack slowed and stalled as losses mounted, ammunition ran short and exhaustion took hold.

The fighting ended largely at dark. Under a full moon, the Confederate leaders discussed their options. Eventually, their commander, Braxton Bragg, decided to withdraw down the backside of Lookout Mountain, a maneuver made possible by a total lunar eclipse later that night. Talk about a lucky break.

This battle exemplified the open wound our nation had become. Civil Wars are always brutal and deeply painful experiences. This moment in the pro-Union area of Tennessee put all of that brutality on display in appalling terrain, under the eyes of thousands of civilians trapped in the siege with the Union Army.

This battle exemplified the open wound our nation had become. Civil Wars are always brutal and deeply painful experiences. This moment in the pro-Union area of Tennessee put all of that brutality on display in appalling terrain, under the eyes of thousands of civilians trapped in the siege with the Union Army.

Over the next few days, as General Sherman and General Thomas struck the Confederate troops on Missionary Ridge across the siege line from Lookout Mountain, thousands of American men and boys died in the most horrific ways imaginable. Shattered wounded lay on the field at the mercy of the over-taxed medical corps and the local civilians.

They fought with exceptional fury here, both sides resolved that they were in the right; the cause was just and worth the risk of their life and limbs.

Yet what I found here wasn’t the tale of brigades moving here and there, the attacks and desperate defense among the rocks. It wasn’t the civilians who suffered or fled or saw their fields filled with the dead or dying.

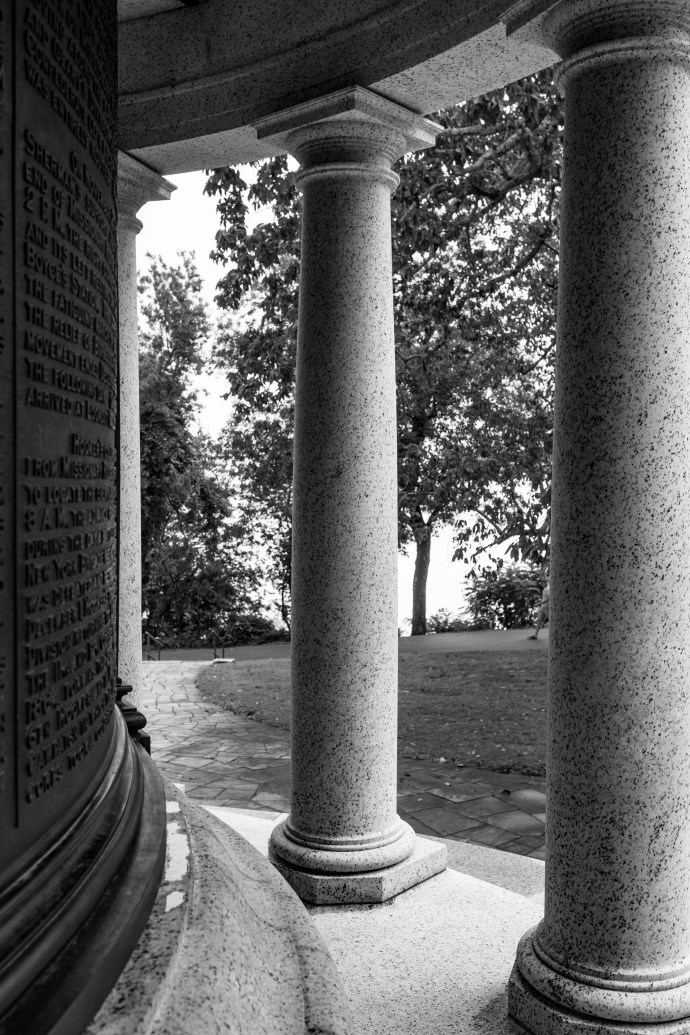

The story I found on Lookout Mountain was one of forgiveness and reconciliation. In 1907, the New York veterans of the battle returned to Tennessee and commissioned the construction of a monument that now dominates the battlefield park. Eighty-Five Feet above the mountain’s summit, two soldiers stand. One Union, one Confederate, they are cast in bronze shaking hands under an American flag.

The story I found on Lookout Mountain was one of forgiveness and reconciliation. In 1907, the New York veterans of the battle returned to Tennessee and commissioned the construction of a monument that now dominates the battlefield park. Eighty-Five Feet above the mountain’s summit, two soldiers stand. One Union, one Confederate, they are cast in bronze shaking hands under an American flag.

The base of the monument is made with a mix of Massachusetts granite and Tennessee marble, blended together as a symbol of the reunion and rebirth of our nation after so much suffering.

The base of the monument is made with a mix of Massachusetts granite and Tennessee marble, blended together as a symbol of the reunion and rebirth of our nation after so much suffering.

Here, a generation made a statement for all future Americans. The victory won in East Tennessee and earned in the blood of their comrades was not the point of remembering this battle. The point was the future, and for that to be a prosperous one, these men put aside the pain, the hostility, distrust and political divisions that tore this country apart and set it on a path of terrible slaughter. They forgave. Former foes became fellow Americans once again.

This is the New York Peace Monument, and as I stood within it, reading the bronze plaques that can be found inside its columns, it struck me that the courage required to reach out and forgive probably took as much emotional courage as assaulting up Lookout Mountain required in their youth.

Today, we are at a crossroads where hate and political animosity dominate our news cycle. Every day, I read about college professors calling for the President’s murder, or of calls by radio personalities like Michael Savage for civil war should the President be removed from office. The talk from both sides is shrill, violent. Destructive.

At Lookout Mountain, the generation that experienced civil war gave us a legacy of peace and reunity. I hope we have the courage, grace of forgiveness, and acceptance of our differences to preserve that legacy. If we don’t, I fear we will lose everything about our nation that has made us great.

Last week, I was supposed to only be at Oshkosh for Monday and Tuesday. I ended up staying until Sunday morning, shooting photos on the flight line for up to fifteen hours each day. I was simply amazed at the diversity of aircraft coming and going in the morning, long before the official air show began. Seriously, if you love aviation, get to Oshkosh sometime in your life if you’ve never been. It is the holy grail of warbird events.

Last week, I was supposed to only be at Oshkosh for Monday and Tuesday. I ended up staying until Sunday morning, shooting photos on the flight line for up to fifteen hours each day. I was simply amazed at the diversity of aircraft coming and going in the morning, long before the official air show began. Seriously, if you love aviation, get to Oshkosh sometime in your life if you’ve never been. It is the holy grail of warbird events.

Last week was a very special one for me. After finishing up doing research at the Richard Ira Bong Veterans Historical Center in Superior, I drove south to Oshkosh, pitched a tent and spent five days photographing the aircraft.

Last week was a very special one for me. After finishing up doing research at the Richard Ira Bong Veterans Historical Center in Superior, I drove south to Oshkosh, pitched a tent and spent five days photographing the aircraft.

Day 1 of my cross country research road trip for my next book took me to the Eastern Oregon desert, where I had a chance meeting with an OIFIII veteran.

Day 1 of my cross country research road trip for my next book took me to the Eastern Oregon desert, where I had a chance meeting with an OIFIII veteran. On April 22, 1934, a 39-year old man died of pneumonia outside of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. To his neighbors who watched as the family house fell into disrepair, was finally boarded up and abandoned in the depths of the Depression, the owner was an oddball sort of man who never fit into their community. He was seen drinking alone on his porch, and in his final years alcoholism wrecked both his health and most of this relationships.

On April 22, 1934, a 39-year old man died of pneumonia outside of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. To his neighbors who watched as the family house fell into disrepair, was finally boarded up and abandoned in the depths of the Depression, the owner was an oddball sort of man who never fit into their community. He was seen drinking alone on his porch, and in his final years alcoholism wrecked both his health and most of this relationships. This was the tragic last act in the life of Lieutenant Colonel William Thaw, the first American to fly in air combat. He became a national hero during World War I, first while as a Soldier in the French Foreign Legion, later as a member of the all-volunteer American squadron called the Lafayette Escadrille, which fought for the French long before President Wilson asked Congress to declare war on the Central Powers. Later, as the United States Army Air Service reached the Western Front in 1918, he commanded the 102nd Aero Squadron. He served with great distinction and was awarded two Distinguished Service Crosses, the Legion of Honor and the Croix de Guerre while being credited with five German planes downed.

This was the tragic last act in the life of Lieutenant Colonel William Thaw, the first American to fly in air combat. He became a national hero during World War I, first while as a Soldier in the French Foreign Legion, later as a member of the all-volunteer American squadron called the Lafayette Escadrille, which fought for the French long before President Wilson asked Congress to declare war on the Central Powers. Later, as the United States Army Air Service reached the Western Front in 1918, he commanded the 102nd Aero Squadron. He served with great distinction and was awarded two Distinguished Service Crosses, the Legion of Honor and the Croix de Guerre while being credited with five German planes downed.

These are all human costs of war; ones that rarely makes the history books as they are difficult to face and discuss. But we need to have a conversation about them, because it is an after-effect of every war this country has fought. Before we send our men and women into battle, our nation’s leaders must recognize the long-term effect it will have on some of the families and communities that send their loved ones off to war. It must be a factor when deciding whether or not the crisis at hand merits the use of force. Once the decision is made to send in the troops, we must have in place a better and more robust structure to support those who return home. In the last sixteen years of war, we have a spotty record at best of doing that, and the toll has been a heavy one as a result.

These are all human costs of war; ones that rarely makes the history books as they are difficult to face and discuss. But we need to have a conversation about them, because it is an after-effect of every war this country has fought. Before we send our men and women into battle, our nation’s leaders must recognize the long-term effect it will have on some of the families and communities that send their loved ones off to war. It must be a factor when deciding whether or not the crisis at hand merits the use of force. Once the decision is made to send in the troops, we must have in place a better and more robust structure to support those who return home. In the last sixteen years of war, we have a spotty record at best of doing that, and the toll has been a heavy one as a result.

The VC reached the perimeter and swarmed over some of the APC’s. The tracks buttoned up and their commanders called for “dusting”–canister shots directed at their own vehicles by their fellow troopers. The idea was these shrapnel shells would kill the VC around the tracks but be unable to penetrate the M-113’s armored hulls.

The VC reached the perimeter and swarmed over some of the APC’s. The tracks buttoned up and their commanders called for “dusting”–canister shots directed at their own vehicles by their fellow troopers. The idea was these shrapnel shells would kill the VC around the tracks but be unable to penetrate the M-113’s armored hulls.